(Hit Ctrl+ to read this journal entry).

Here’s the piece I was listening to as I wrote this:

You can read more about Quiquern here.

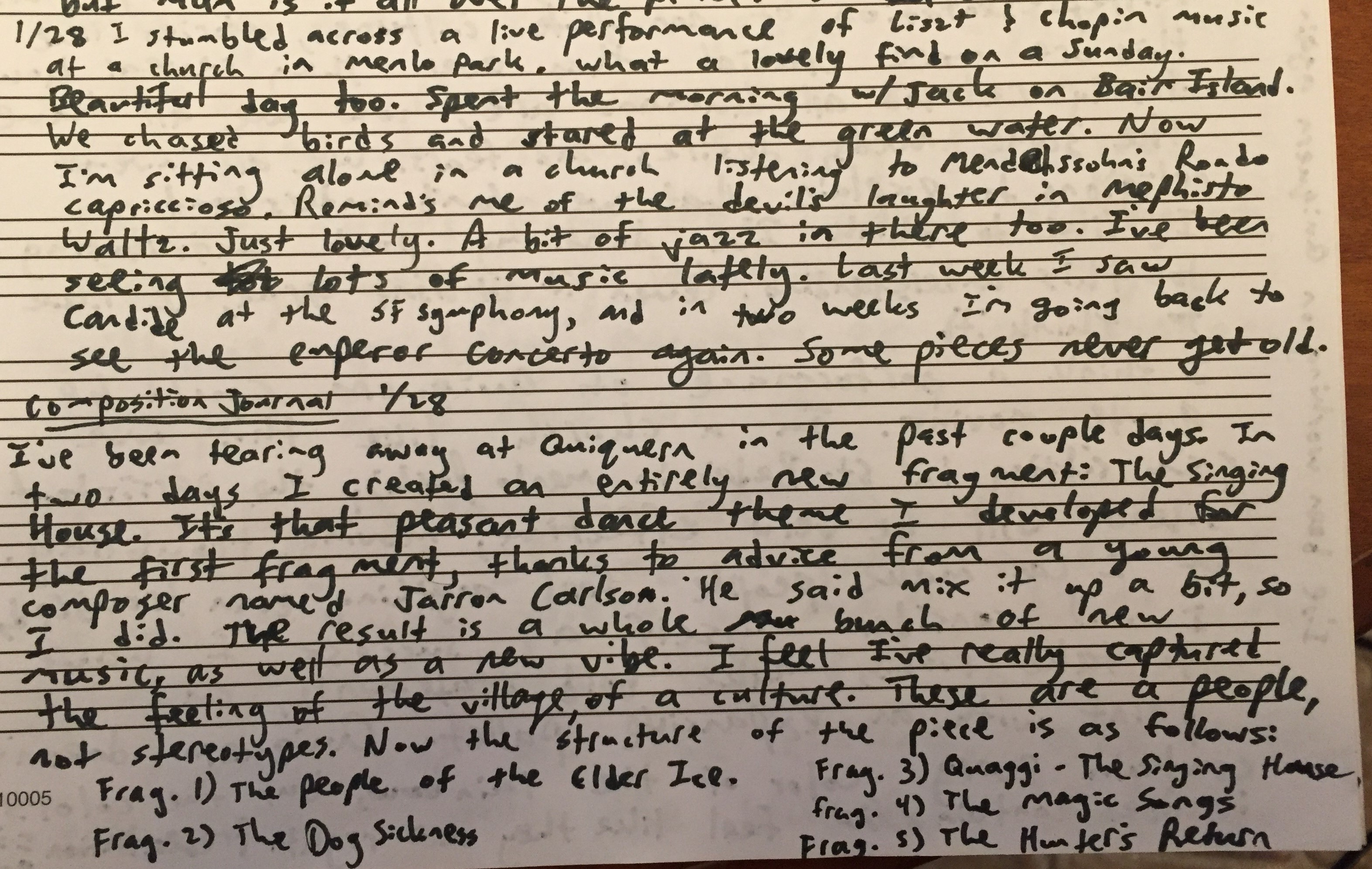

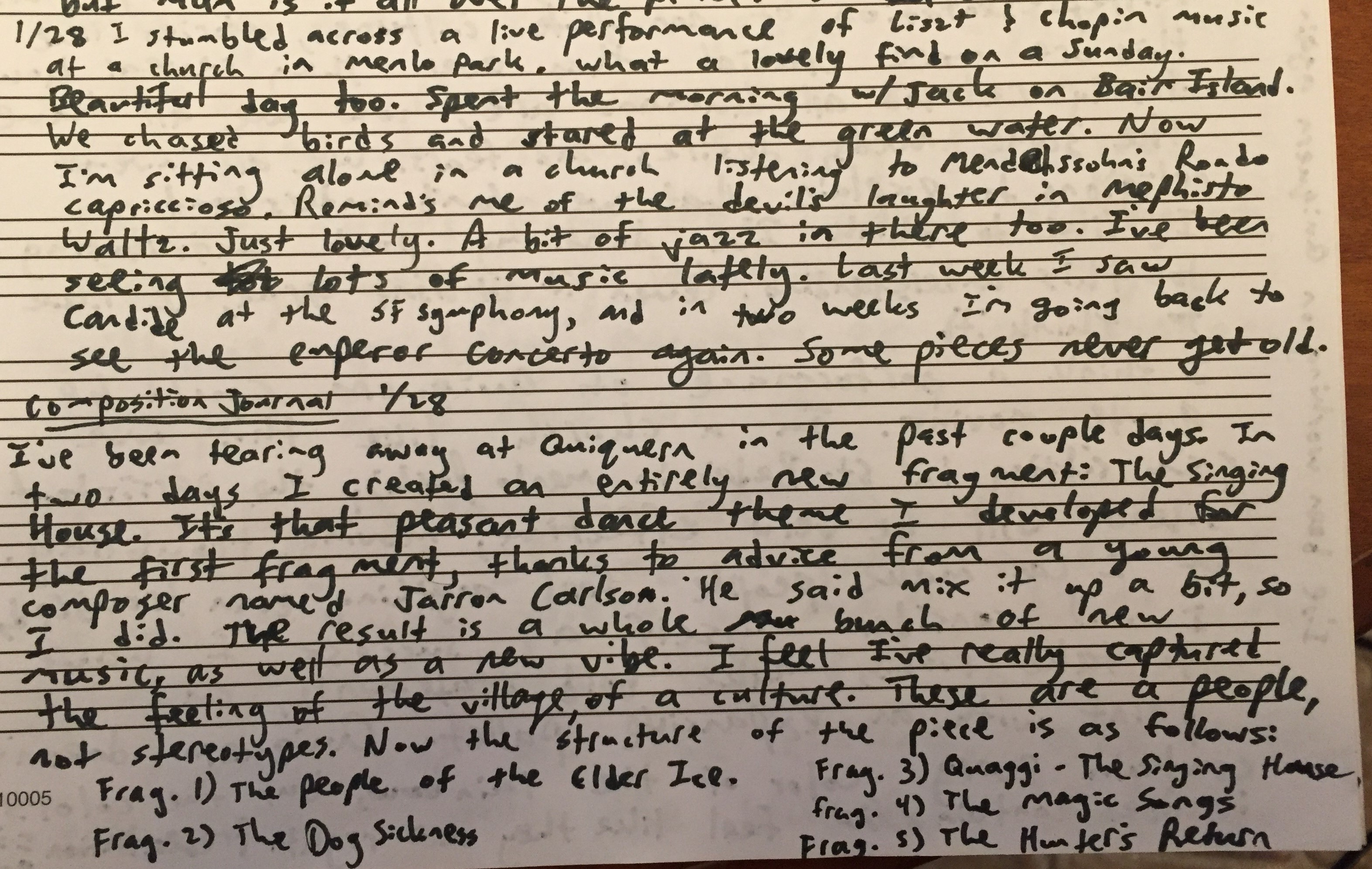

Seeking balance in a chaotic world

(Hit Ctrl+ to read this journal entry).

Here’s the piece I was listening to as I wrote this:

You can read more about Quiquern here.

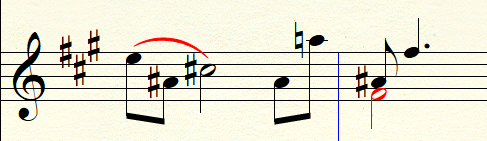

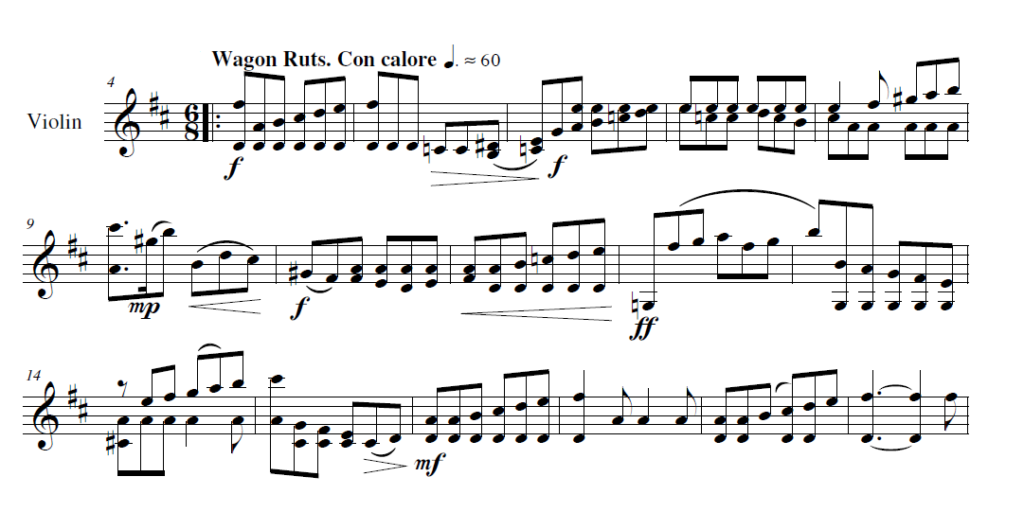

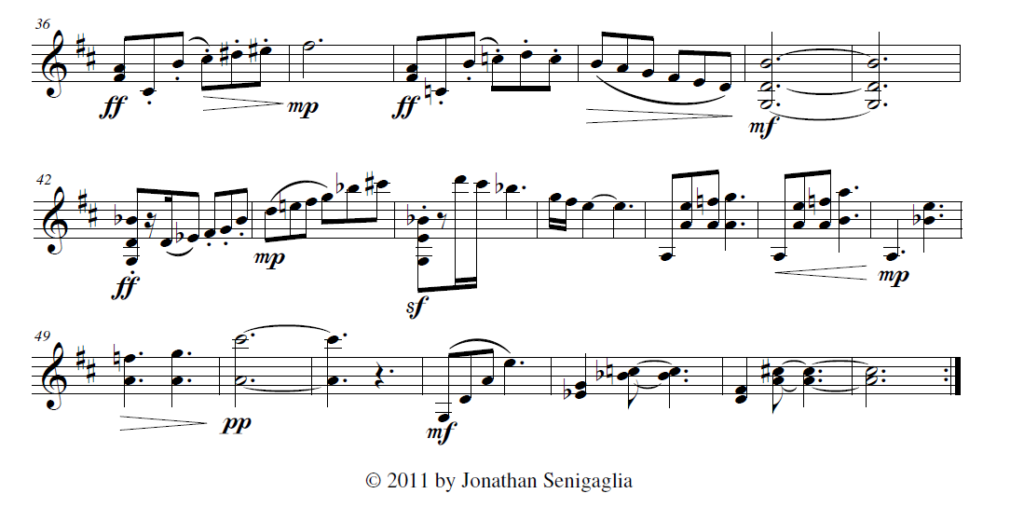

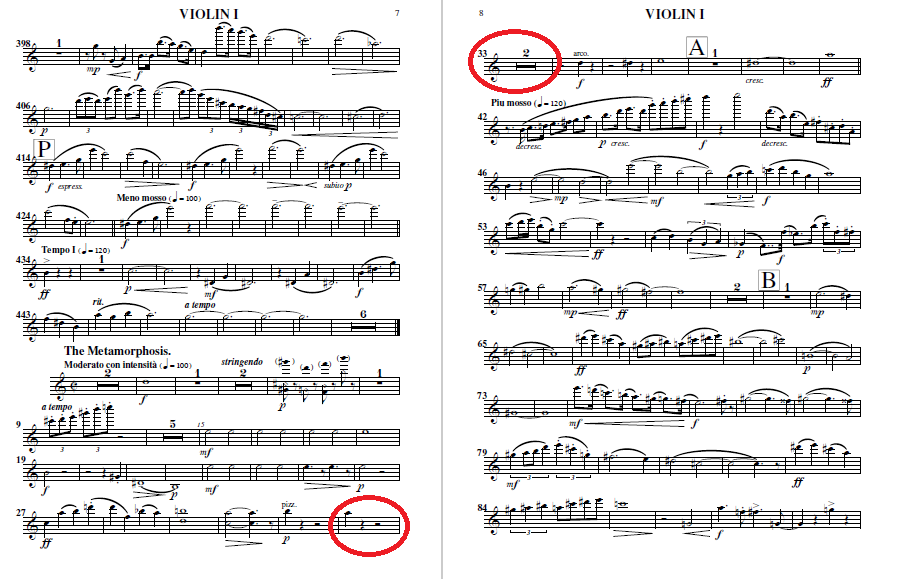

Today I finally completed part two of my piece called “Quiquern.” This movement is called “The Dog Sickness”. (Click here for part one).

I thought “Quiquern” was complete years ago. Time and again I would declare it officially finished. But then, months later, something just wouldn’t sit right with me. I’d pry it open again and tinker with its innards. Maybe it will never be done. Maybe I’m destined to dance with this score til the end of my days.

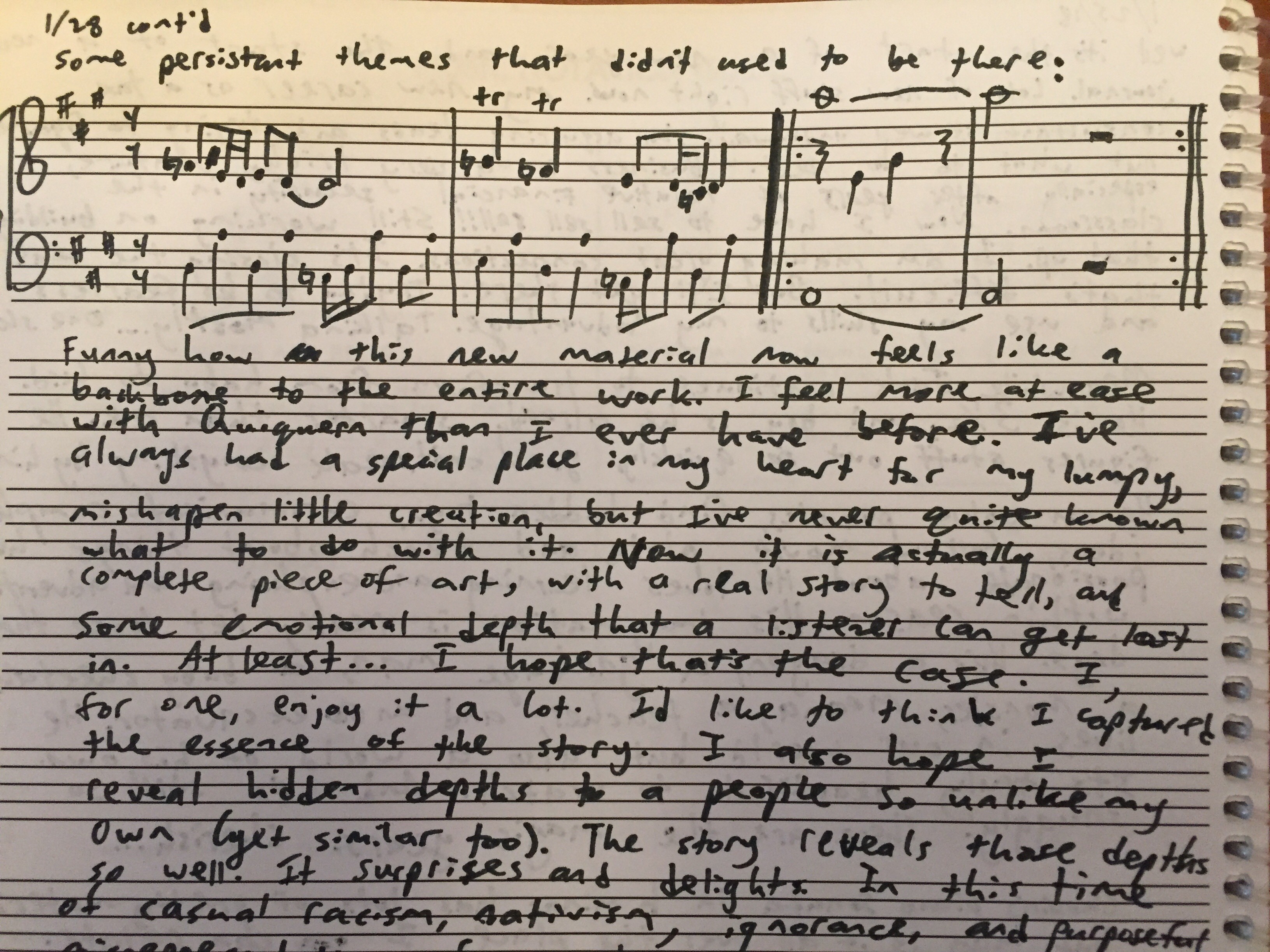

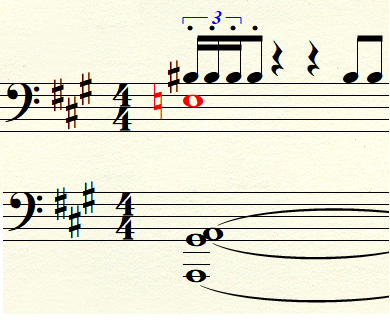

Don’t get me wrong, I have always loved this music. Every time I pick it up again, I’m reminded of why I have such a sweet spot in my heart for “Quiquern”. It evokes so many positive memories: of writing it over Christmas break in San Diego, of reading The Jungle Book over and over, of experimenting with new sounds (new to me anyways), of unhinging my creativity from purely classical harmonies and letting go a bit. Like this sort of thing:

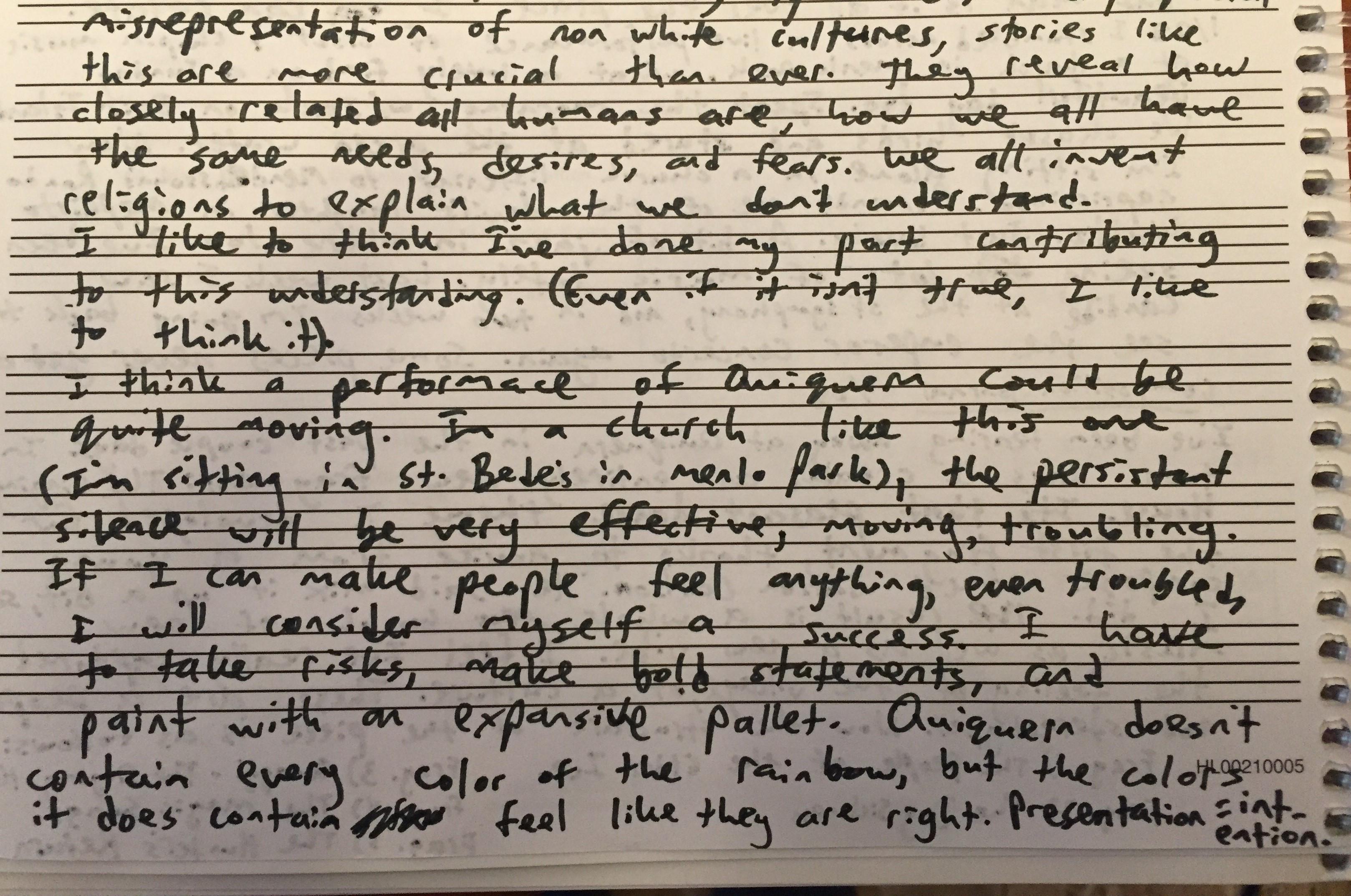

I never go full atonal, I’m always chained in some way to classical forms and progressions, but this piece freed me up in some ways I had never tried. I went wandering a bit through the cold wilderness. I let the images in my mind solidify into a color palette. I focused on the story the sounds told, rather than fussing about the progression. This allowed me to express all the pain I felt after reading that beautiful, heart-breaking story.

So why, if this music was so compelling, couldn’t I call it “complete”? Well there were a few reasons. One is I just wasn’t thinking about form when I first wrote it. I was in “crank it out” mode, writing down whatever ideas popped into my head. I tried to free up my creative process and stop self-editing as I wrote. As a result, the music flowed pretty freely out of my brain, and the harmonies were weirder than I was used to. The musical nuggets that emerged were captivating and exotic. But there was no overarching shape to the piece. It was just idea after idea, with very little connectivity. Throwing a bunch of nuggets into a pile don’t make it a whole chicken.

This time around I wanted to work on that. This is the sort of pre-thought that Schoenberg went on about. In other words, real composers think about form and structure BEFORE writing, they don’t just wander around in the dark hoping to bump into a complete form. When I put some thought into this piece, I was able to picture the arc that I wanted to create with the music. A chaotic, hallucinogenic dream sequence, sandwiched on either side by a poignant but solitary theme calling out in the dead stillness of the ice-fields. Perhaps the middle is what the dogs feel as they begin to starve, giddy and terrified and angry; the beginning is what the Inuits feel watching their beloved animals suffer in the dark, knowing what awaits them if another source of food is not found soon. Or maybe the beginning is a song for a way of life that is slowly dying.

Prayers to a cruel and fickle ice god.

And while I was working on form, I also put more thought into motifs. This piece has a lot of rich material, maybe even too much. Though I love that there are so many fun ideas in there, sometimes it plays like one of those Beatles songs with too many good ideas but no development. This time around I went through the piece with a needle and thread, and wove my favorite motifs into the very fabric of the piece. In and out they come, appearing and disappearing again, becoming more recognizable with each appearance. Just as a chef might pour a bit of the boiling gnocchi water into the sauce to bind all the flavors together, my goal was to bind all the ingredients of this music together into something coherent (and tasty).

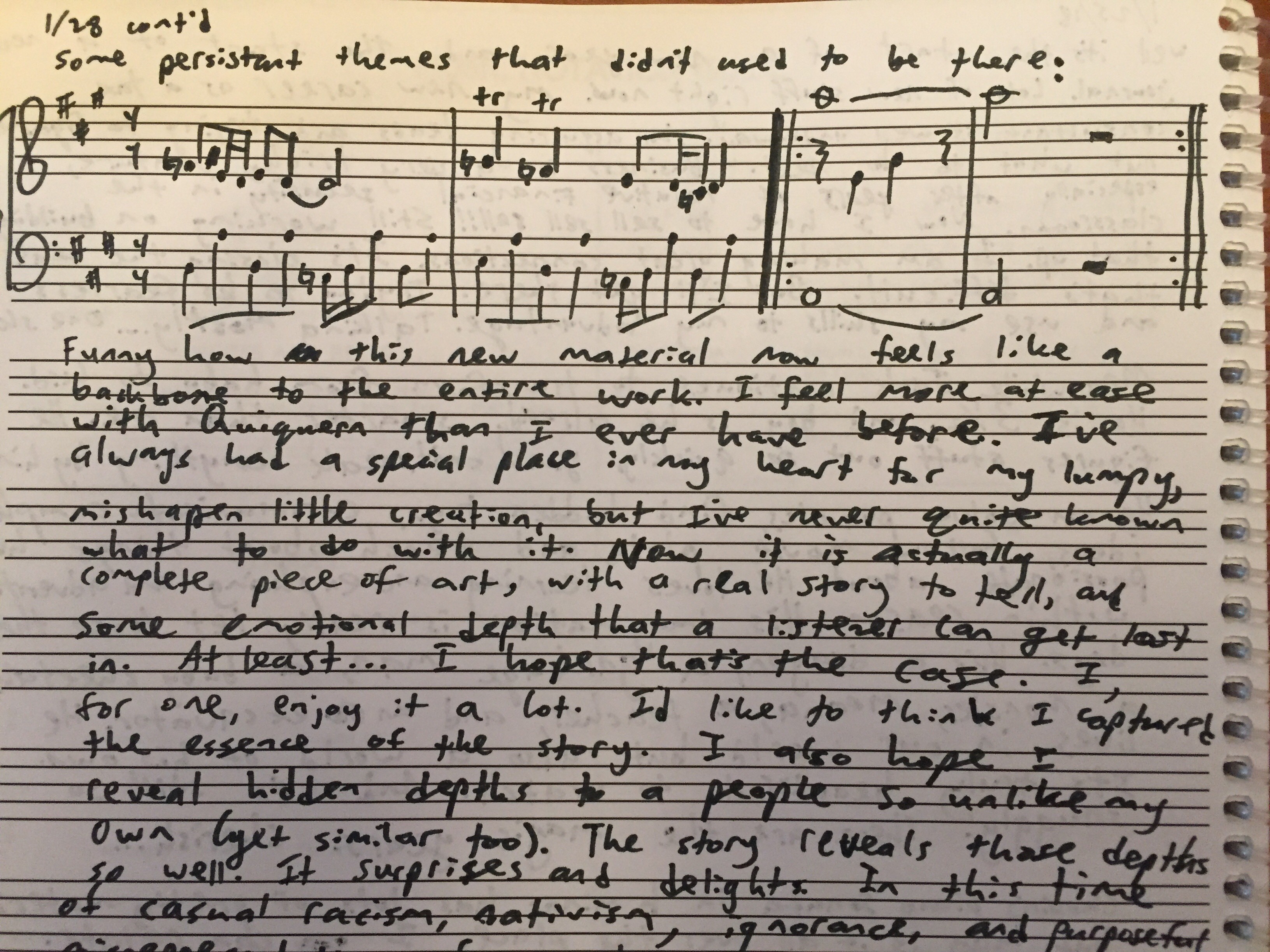

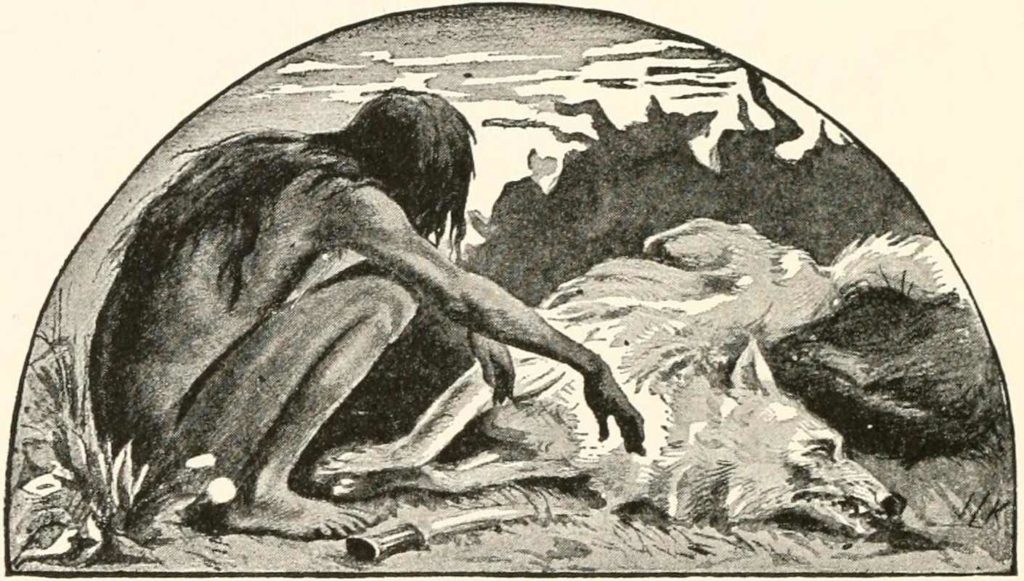

Like this motif, which appears everywhere:

Or this rhythmic motif:

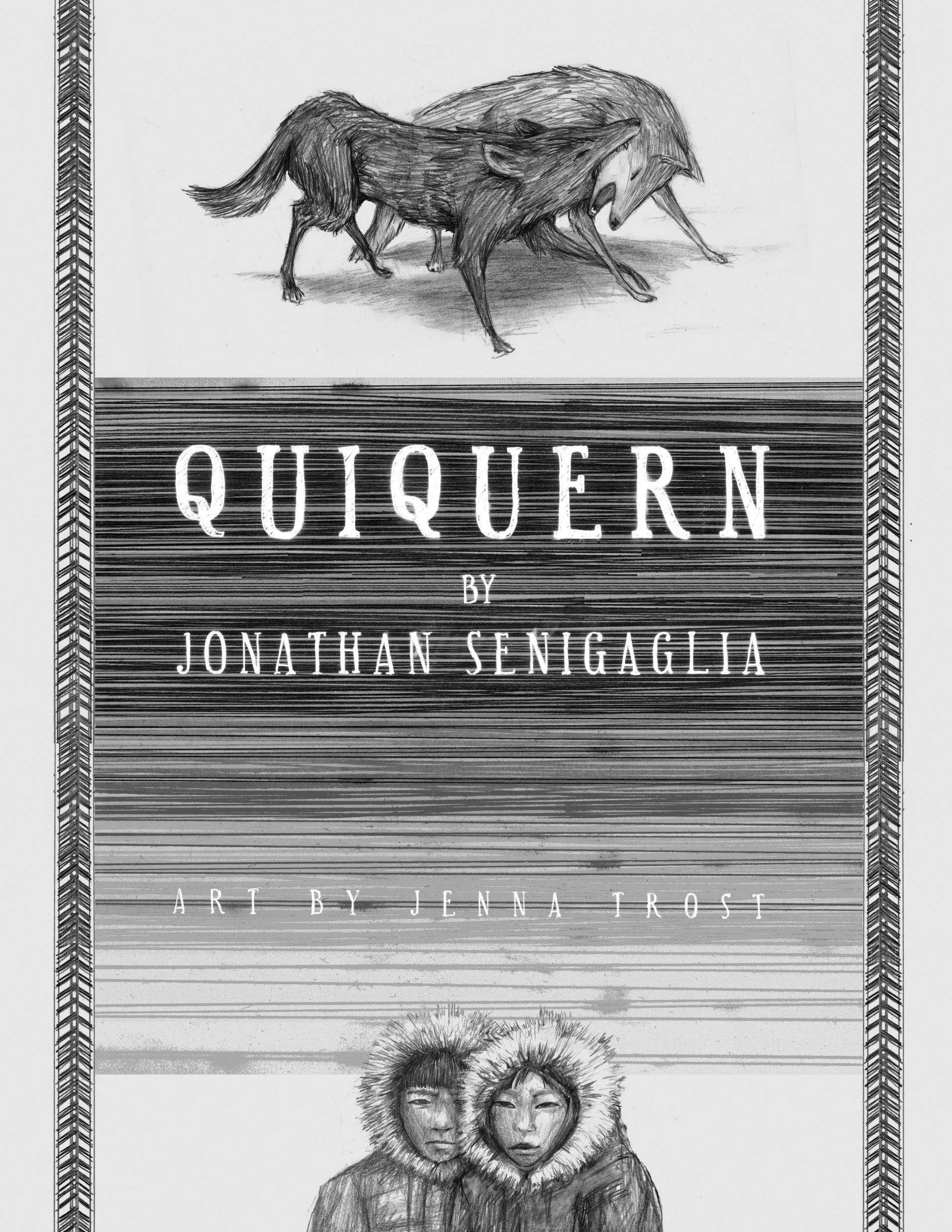

There was something else fundamental that needed retooling: instrumentation. Originally I chose three flutes and piano for this piece, because the flutes evoked the lonely, frozen tundra. But as I was writing, I didn’t pay enough attention to the limitations of the flute. I wasn’t writing in an idiosyncratic way, I was just cranking out music. The used a lot of low C’s on the flute because I liked the sound, but I knew the notes were ringing out stronger in my head than they would on a real instrument, where that low C is easily covered up and lost in the mist. I considered an alto flute, but decided a clarinet would give me a whole other palette to play with.

When one phases in a new instrument like this, one can’t just paste the flute part into a clarinet staff and call it done. The addition of the clarinet changed the whole character of the piece. While the flute is cold and isolated and graceful and metallic, the clarinet is like warm baking bread. It’s also intense, frenetic, a bit insane at times, with low earthy tones that can feel angry or foreboding or subdued. That new voice greatly expanded the range of the piece, so I was able to open the music up a bit and let it breathe.

All these forces combined into something much different than the piece I’ve been kicking around all these years. This version feels like a completed piece of art. It’s not just a sketchbook of ideas, it’s a story arc with real meaning. In other words it really does feel done. For real this time. Seriously.

This music is about suffering, and in a way the audience suffers a bit as they listen. It is not over quickly. But the music is also about hope, and the idea that suffering is a part of life, and doesn’t necessarily cancel out the good. There are joyful memories mixed in with the pain. There is a dream that soon the pain will end. Yes there is fear, yes there is chaos and anger. But the sun still rises at the end, even if the air all around is frigid.

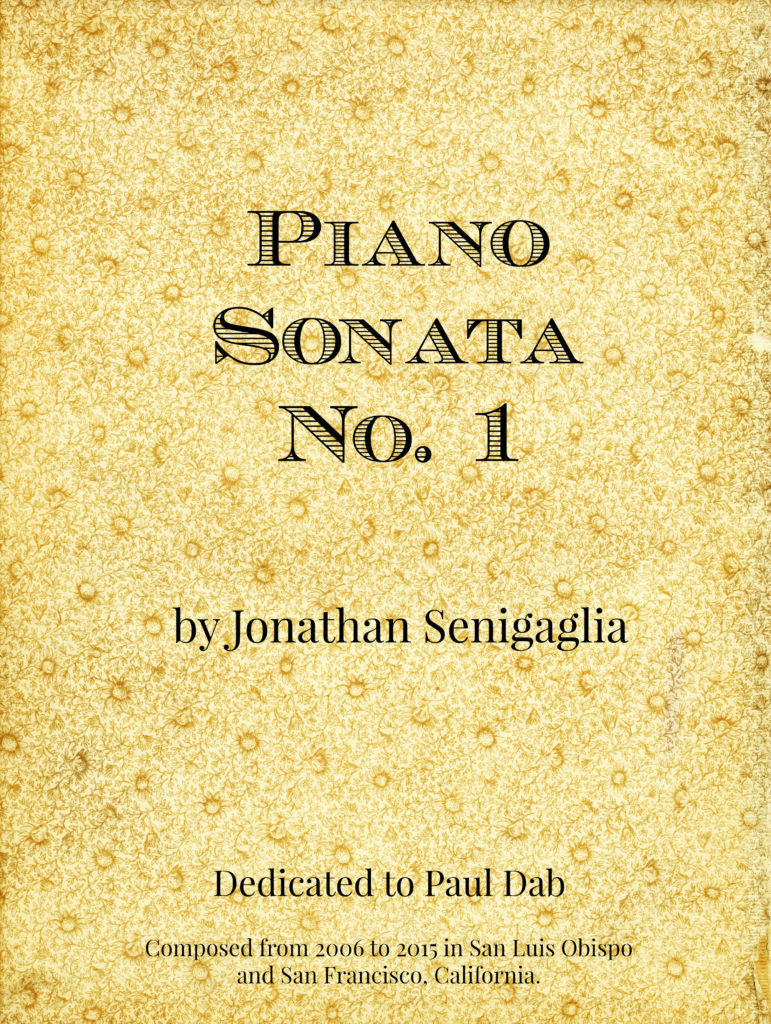

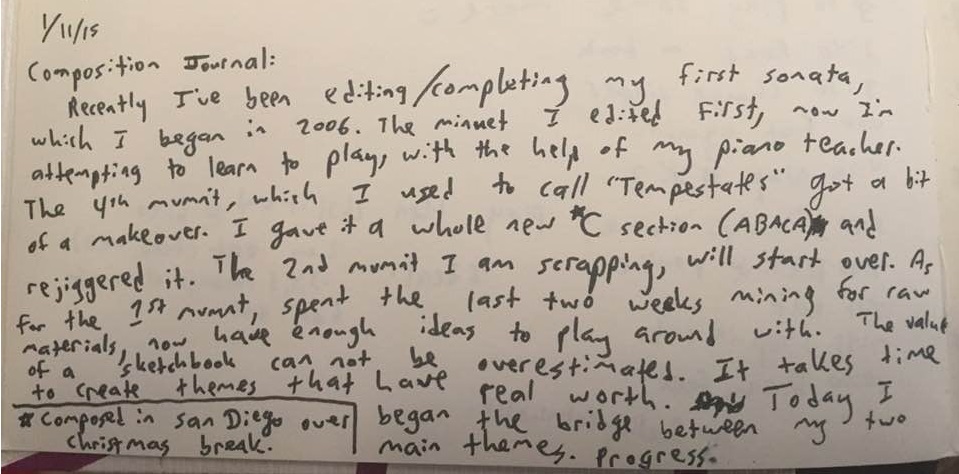

My first piano sonata took me over a decade to complete. Then Jack showed up and POOF, it was done! Strange how that happens.

I always call this piece “Jack’s Sonata”, but half of the music actually predates Jack by some time. In fact, the last two movements are my earliest completed piano music. I was working on the first drafts all the way back in 2006, maybe earlier, when I was still living in the dorms at Cal Poly, a time when I knew I wanted to be a composer but had no idea how to actually write music. I remember so clearly the frustration of having music in my head, but lacking the skills to notate it. Hence, I started this music with the best intentions, but quickly became frustrated when I couldn’t finish it and tossed it in the ash heap. Luckily my ash heap is just a folder on my laptop, so the music was easily resurrected. By the time I picked it up again 10 years later, I was more properly equipped to complete the task.

So why does this music belong to Jack if it was begun long before he was born? Because Jack got me to finish it. I write such better music when I have something meaningful to write about, and there’s nothing more meaningful than the birth of my first child. The gaps I had left in the music over the years were suddenly filled in by the waves of emotion I felt as a new father. Usually I write slowly and methodically, but Jack’s presence in my life lit a fire under me and kicked off an avalanche of creative activity. Jack gave me so many new things to think about, new ways of looking at the world, new experiences. Holding a newborn brought on such a strange combination of intense love and intense uncertainty, and all of that worked its way into my music. So even though the music is older than Jack, in a certain way he owns it. I’m not sure I ever would have finished it if it wasn’t for him. His little face is imprinted on every note.

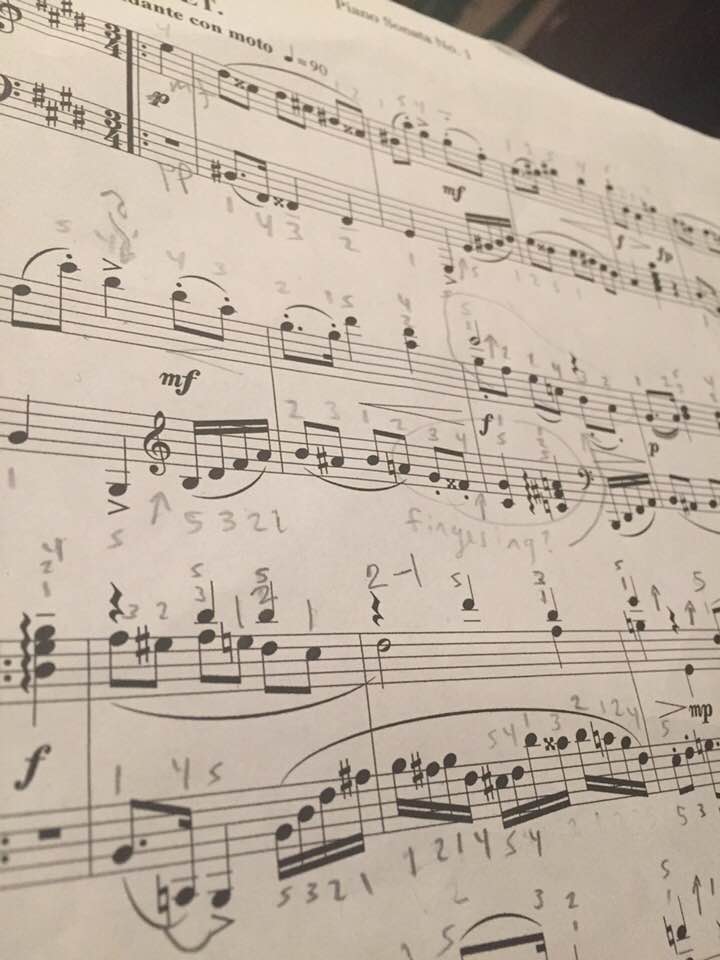

Paul Dab, my former piano teacher, also owns a piece of this music. When it comes down to it, I had fallen out of love with the piano, and Paul rekindled that fire. He made me excited about the instrument and showed me new ways to explore it. That excitement drove me to finally finish this sonata (including the composition of two brand new movements from scratch). Paul showed me how to think like a pianist again. I put my hands back on the instrument after a long hiatus, not just to tinker with chords but to play, play, play! He gave me the tools to improve my technique, both as a performer and composer, and he showed me how to write idiomatically for the piano, something that is often forgotten when writing music directly into the computer. This work would not exist in its current form without his guidance. Therefore, even though I always call it “Jack’s Sonata”, it is officially dedicated to Paul Dab.

Movement 1: Allegro con brio

Here’s what the first movement sounds like (computer rendition):

You might be thinking, “hmmm that sounds a little minor. I thought he said it was about his newborn son.” Well, yes and no. It was written right after he was born, but it’s not really ABOUT him. It’s really about me! It’s my musical reaction to some crazy-ass change happening in my life. It’s a burst of creative energy as my whole life gets flipped upside down. I think it’s fear of the unknown. It’s everything I felt when I held that precious, tiny, fragile, little nugget and pondered my place in the universe. This is an example of some music that just poured out. I had a lot of things to work out, and writing music is excellent therapy.

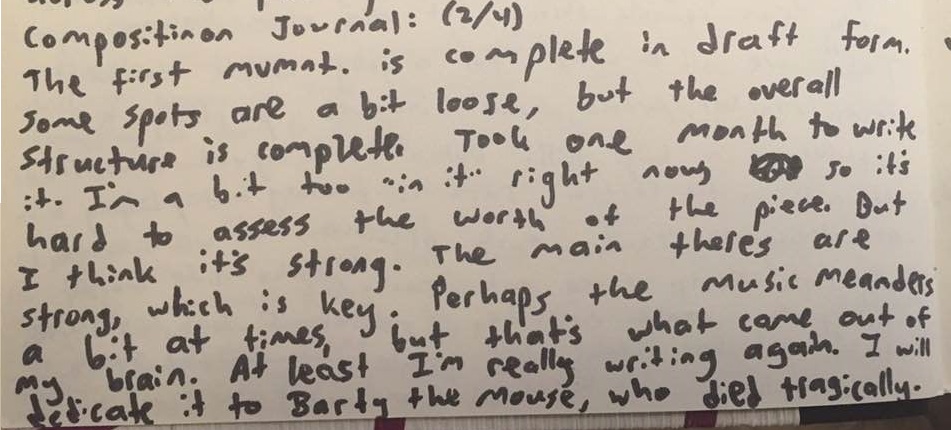

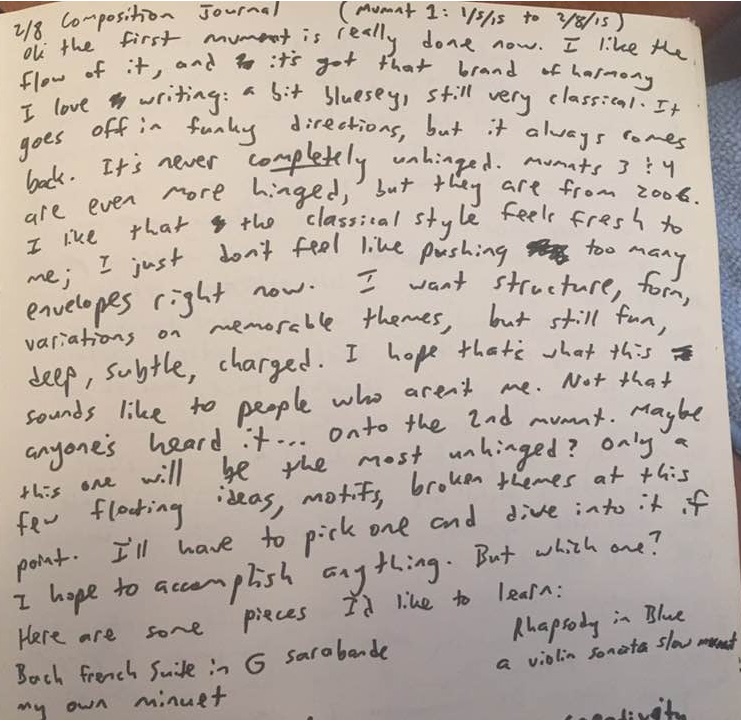

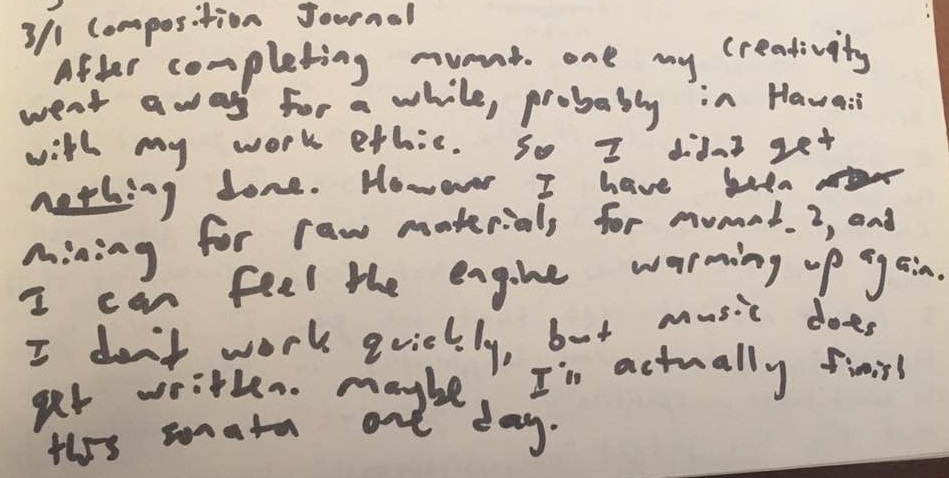

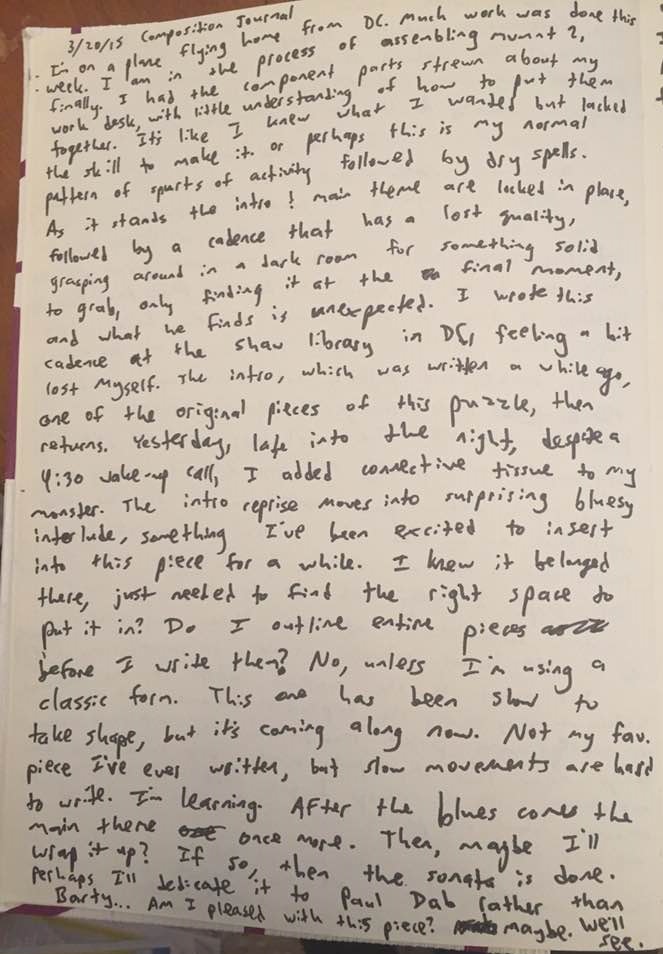

That being said, I still had to put a whole lot of thought into this movement. I spent hours and hours at the library hashing and rehashing ideas, experimenting and prototyping and testing ideas and staring blankly at the wall. Originally I had written an entirely different first movement way back in 2006. But when I picked this music back up in 2014, I realized that that whole thing had to go. There may have been some salvageable ideas buried in there, but I couldn’t help but see the whole thing as student work. I tossed it in the trash and started with a blank page. The music that came out of my brain belonged entirely to Jack.

This movement is highly structured, though it might not seem that way at times. Straight-forward, good old-fashioned sonata form. Ok, maybe not too old-fashioned. But really, it follows the same basic structure as the first movement of most Beethoven sonatas: Theme 1 in tonic, theme 2 in either dominant or (in this case) mediant, followed by an unstable gobblety-gook of the two themes all mixed around and intertwining, leading finally back to the first theme again in the tonic, and the lastly the second theme now transposed to the tonic. So though it may sound at times as if it contains a hundred different unconnected ideas, I assure you it is firmly rooted in classical forms.

For a first movement of a sonata, the music has got to be catchy, a bit flashy (but not decadent), and something the listener will want to hear again. For the first theme I got hooked into this angsty minor bluesy vibe that keeps falling into a mellow waltz. It can’t really make up its mind on what it wants to feel. The slightly slower second theme is cleaner, with a bass line reminiscent of a rock riff. I often find myself absent-mindedly humming this theme. It’s chipper, skippy, but never entirely major. Slices of it almost give off a pop vibe, though I made sure to end it on a sour note. These two themes are a microcosm of my psyche at the time.

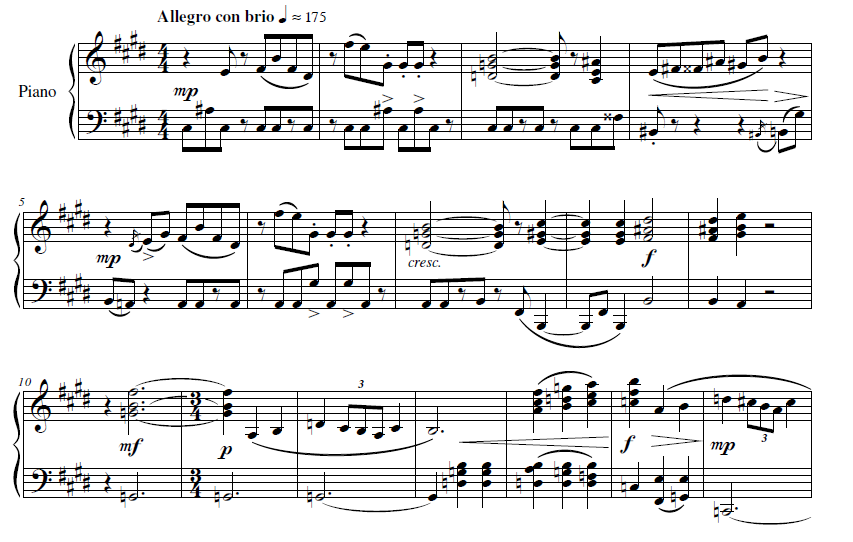

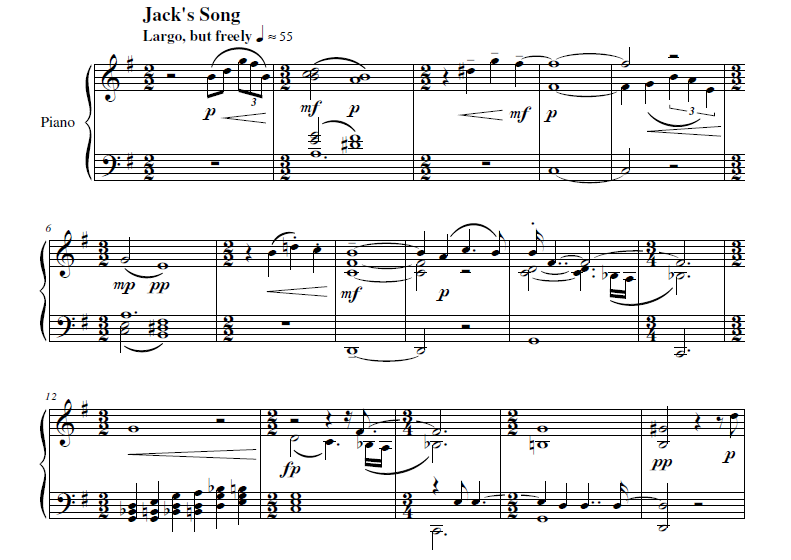

Movement 2: Largo, but freely (“Jack’s Song”):

Here’s a computerized version:

And here’s a live performance from pianist Jun Cai, a student at the SF Conservatory (notice how much more flexible Jun is with the rhythm than the computerized version. There are infinite ways to interpret a piece of music):

This second movement truly does belong to Jack. As this music began to take shape, I was thinking a lot about what it means to be a father, which means my child shaped it. This music is a projection from my mind at the time, a reflection of my emotions and questions, my fear and love. The music fades in and out of coherency, at times directionless, until it finally lands on solid ground. It’s asking a question, and just as the answer comes within reach, it slips away again. This movement is tough to pin down, difficult to categorize. The music is searching, searching… It emerges slowly, pops in and out of view, like a distant ship in the mist. Sometimes it’s a love song, sometimes a lament, sometimes a hopeful look toward the future, and sometimes a lonely figure grasping for something in the dark.

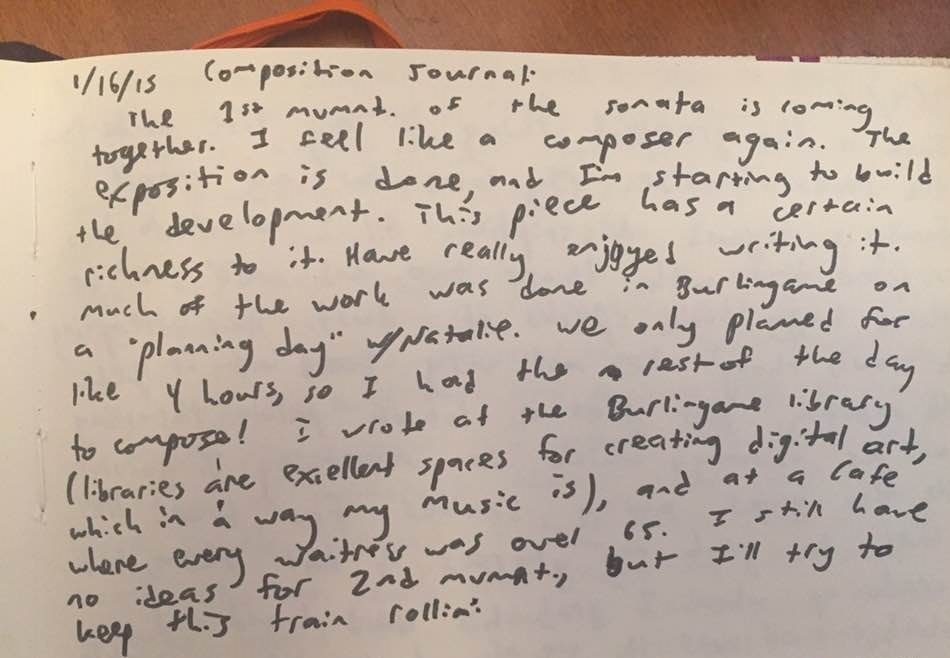

I wrote a good chunk of this music in libraries, specifically the Richmond Library in SF and the Shaw Library in Washington DC. The whole ambiance of the library worked its way into this music. Libraries are bustling with activity: people walking around, searching, questioning, writing, working; children running around and older folks quietly reading the newspaper. Yet it’s also an environment where quiet reflection is of paramount importance. It’s a perfect mix of energy and silence, and I find it a very inspiring atmosphere to write music. This piece also feels to me like it is a mix of quiet and activity. I think this movement is one of my favorite things I’ve ever written… though when I first wrote about this music in my composition journal, I clearly wasn’t sure what I thought about it. (See below for the composition journal).

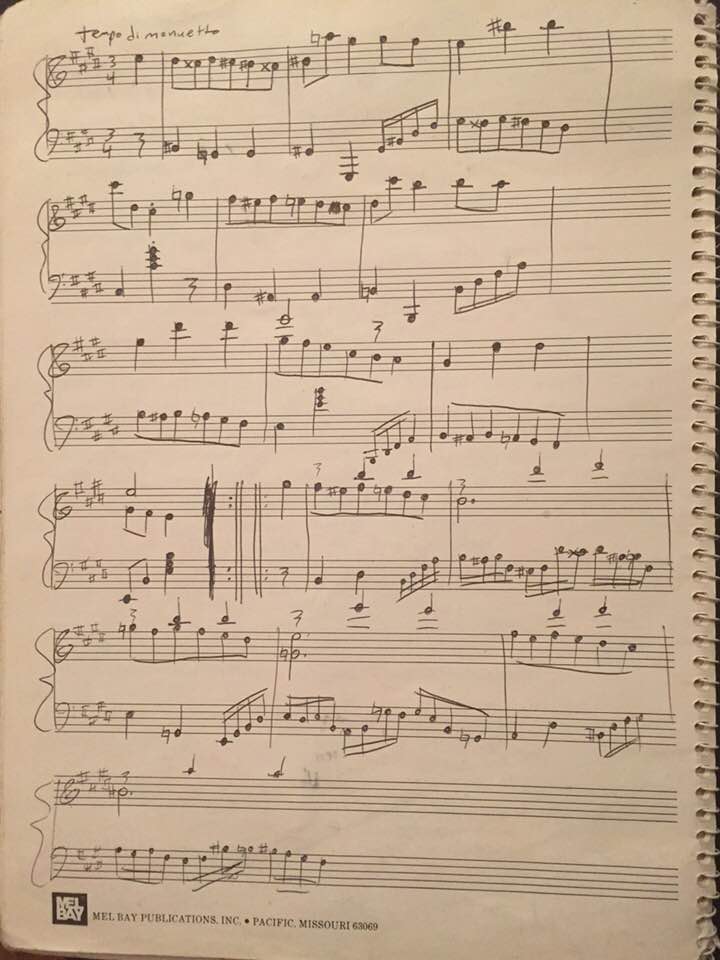

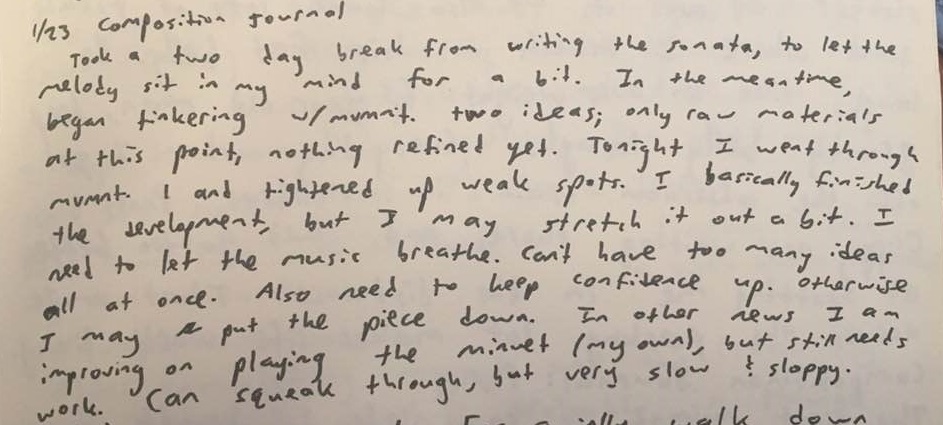

Speaking of my composition journal, reading the entries for this piece reminded me of how crucial sketching is when developing a new piece. I started this movement by jotting down various ideas without editing, then seeing where those ideas led. This was a period of time when the music was coming out rather quickly, and I think sketching had a lot do with that. When I’m feeling something and just need to write music, it is so important that I don’t edit myself, but instead just get everything out. Sometimes I don’t have the time or wherewithal to plan an entire piece in advance. Sometimes I just have to throw paint on the canvas then step back and figure out what shapes I created.

For example, this improv led to an important section in the piece:

And this one became the main theme (listen for Baby Jack in the background):

Movement 3: Minuet and Trio – Andante con moto

Here’ s what it sounds like, computerized:

This movement may very well be the earliest completed piano piece I ever wrote. I’m not sure exactly when I started it, because it predates my habit of keeping a journal. But I think I have a memory of working on it in 2004. I can’t be sure, but it was definitely in a semi-complete form in 2006.

When I revisited this music in 2014, I mainly focused on adding some subtle touches to it (integrating some of the motifs into the fabric of the piece, rethinking dynamics, making it more playable). I originally picked it up again because I was looking for a piece I had written that I might actually be able to play well. This is why I give Paul Dab a lot of credit for inspiring this whole sonata. Once I started tinkering with this old nugget again, I realized I was ready to complete the entire sonata. This is the movement that jump-started it, even though it’s the simplest and more straight-forward movement of the four.

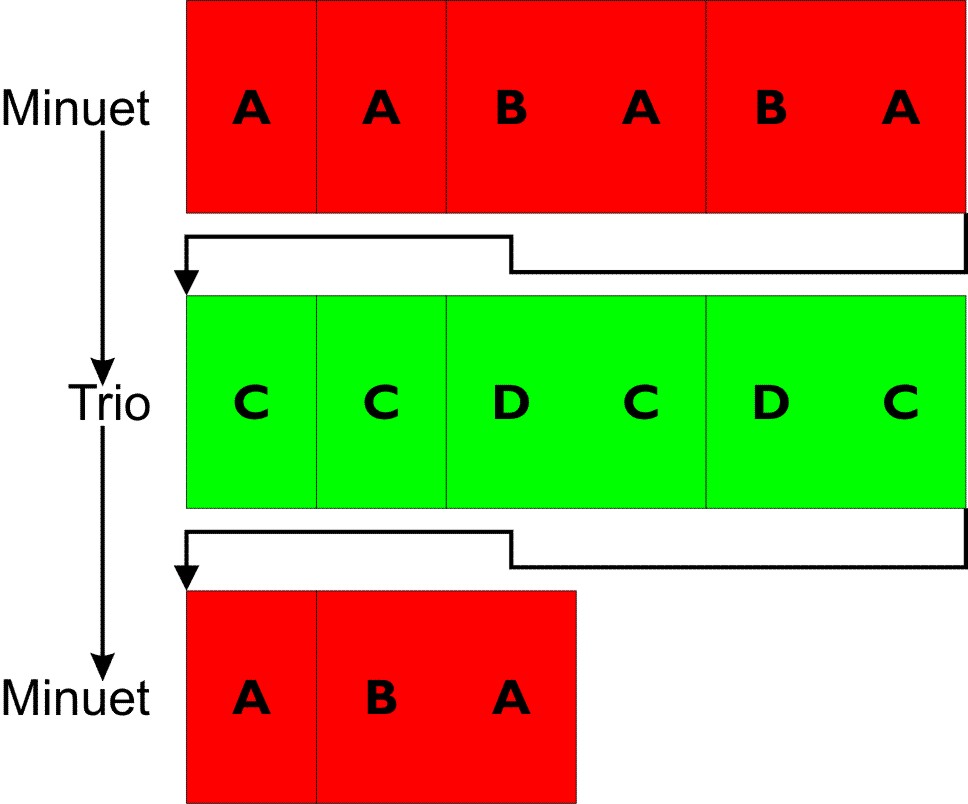

This movement is in a truly classical form: minuet and trio. A short set of Baroque dances, usually inserted into a sonata or symphony, allowed the composer to construct a stately, graceful, low-key moment of rest before the rush of the final movement. Beethoven, Mozart, Haydn and all those dudes used it many times. I really didn’t add much to the structure or push the envelope with this one. It is truly a classical piece, fairly conservative. The form looks like this:

Conservative does not mean bad though. This entire sonata is full of traditional harmonies and forms, yet it still expresses what I wanted to express in that moment. This minuet is more traditional than I would probably write today, but when I started it in 2006 and finished it in 2014, that felt right in those moments. Sometimes going back to basics can unlock all sorts of new ideas.

This piece has a slight drunken quality to it, almost like the music is slurring its words. It gets a bit heated, but in a restrained way. The Trio is a bit angelic, very light, with just a flash here and there of tension. Overall, I don’t want to read too much into this one. Not all music is strictly progammatic music. When it comes down to it, this is a simple minuet and trio. I think I was playing more with form here than with emotion. This little dance is really just a calm interlude before the energetic and weighty final movement.

The minuet is nice to play though:

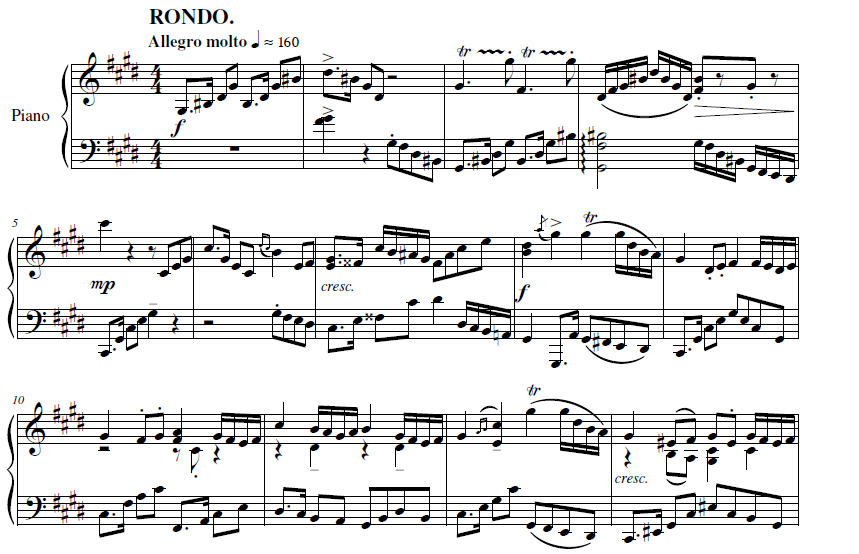

Movement 4: Rondo – Allegro Molto

Here’s what it sounds like (computerized):

This piece is a classic. I have a vague memory of starting it way back in 2003, but I only wrote a few measures before I couldn’t find my way forward. That was when writing a simple chord progression was an uphill battle for me, so this piece was born from pure gut and intuition. Those tools will get you only so far, before technical skill is required to turn a fun little building block into an actual piece. Though I could vaguely hear this music in my head (or at least feel the emotional direction I wanted to take it in), I couldn’t figure out which chords I should use to actually express those vibes. In other words, I couldn’t compose my way out of a paper bag. This tiny nugget was all I had, so I put the piece down for a couple years and focused on learning.

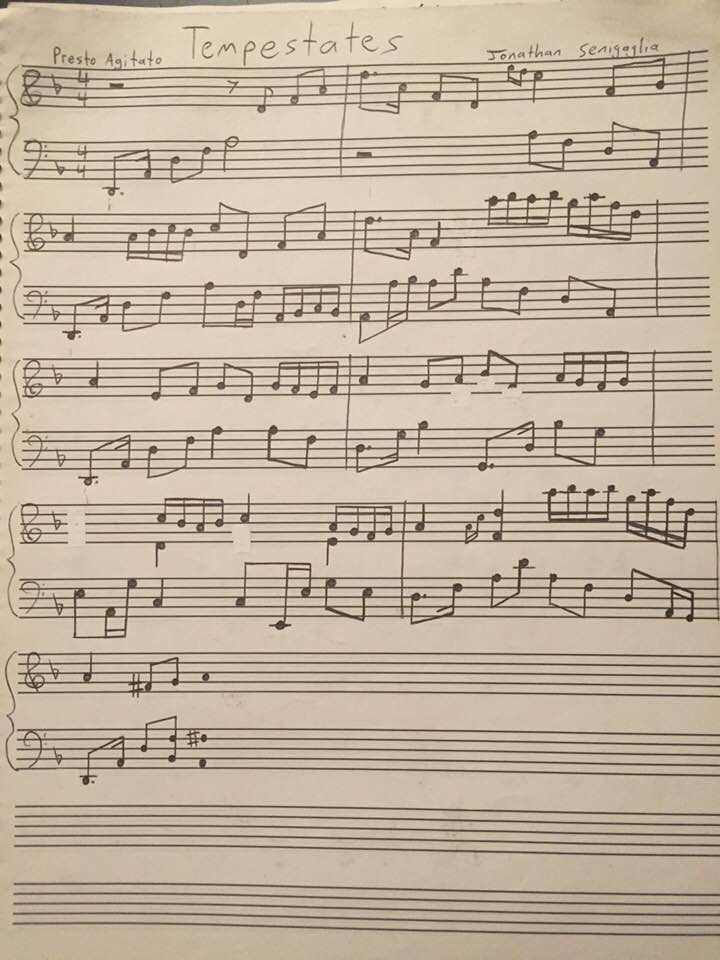

I used to call this music “Tempestates”, I think because I wanted to write a series of pieces about Greek gods or something along those lines. Instead I forgot about this music until 2006, when I was about to begin work on a final project for one of my composition classes. My professor, Meredith Brammeier (who is more responsible for my love of classical theory than anyone else on Earth) suggested that I write a medium-length piece with a clearly discernible form. After pondering my options for a bit, I rediscovered this musical fragment and thought it might make a decent rondo.

Rondo form is another classical form, usually appearing at the end of sonatas and symphonies. It goes something like ABACA, otherwise known as the deli sandwich of classical music.

This piece is very classical-sounding, or early-Romantic to be more precise. Essentially it’s in the style of Beethoven, since that’s who I was obsessed with (still am) when I was writing most of this. Back during that time, when I was still working at the Cal Poly library, I would push the cart of books around the different floors, listening to the entire catalog of Beethoven sonatas on my iPod over and over and over again, until I could hum every movement of every sonata. This Beethoven binge gave me a very strong appreciation of classical form and harmony, but also how to stretch those forms to express something deeper, how to turn form into art. Form is absolutely crucial in classical music, but it can’t be everything.

This movement probably leans more toward form for the sake of form than it does toward pure expression. As a young composer, I think I had to become proficient at form before I could wrap my head around pure expression. But built into this very structured piece is a nice dose of angst, nervous energy, and questioning, the same turbulence that guided the first two movements.

The C section is a soft interlude that plays with a couple motifs we heard earlier in the sonata. But this was not the original C section. I composed the new one mostly over Christmas break 2014 at Erica’s parents’ house in San Diego, on quiet evenings next to the giant Christmas tree, while Erica chatted quietly with her parents in the next room. The old one from 2006 was short, jolly, and fairly tight (not a lot of room to breathe). When I picked this piece up again in 2014, I probably could have expanded that old C section and gave it a bit more flair, but I decided to scrap it and start over. I wanted to write something restrained, quiet, and a bit jazzy, exactly what I wanted to listen to on those chilly winter evenings when the house was quiet.

Here’s the old C section on its own:

It’s got a bit of pep to it, but it doesn’t quite tickle me. I might salvage that one day, but for now it’s on the ash heap with so many other forgotten musical fragments.

Just for fun, here’s a video game version I made a while back:

So that’s about it for my first real-life piano sonata. Is it a perfect piece of music? Absolutely not. The final movement is too tightly wound for my taste. Were I to work on it now, I would stretch it out and let some of the ideas (and the listener) breathe a bit. I do love the first two movements, as they match my more current writing style. But as it stands they don’t exactly fit with the final two movements. This is a lesson I learned while listening to Ozma’s “Double Donkey Disk”: two very different EPs jammed together don’t exactly create an “album”. The two halves of this when taken as a whole do not feel organically written; but instead they resemble a slightly awkward arranged marriage. Which makes sense, considering the two halves were written a decade apart from each other. They are, however, united in one important way: I finished them all at the same time, motivated by the changes fatherhood brought to my life. So though the two halves aren’t necessarily united thematically, stylistically, or even artistically, they are forever united in my memories, and therefore they will remain together for eternity.

Below you will find my composition journal entries for this sonata:

Have a listen while you read:

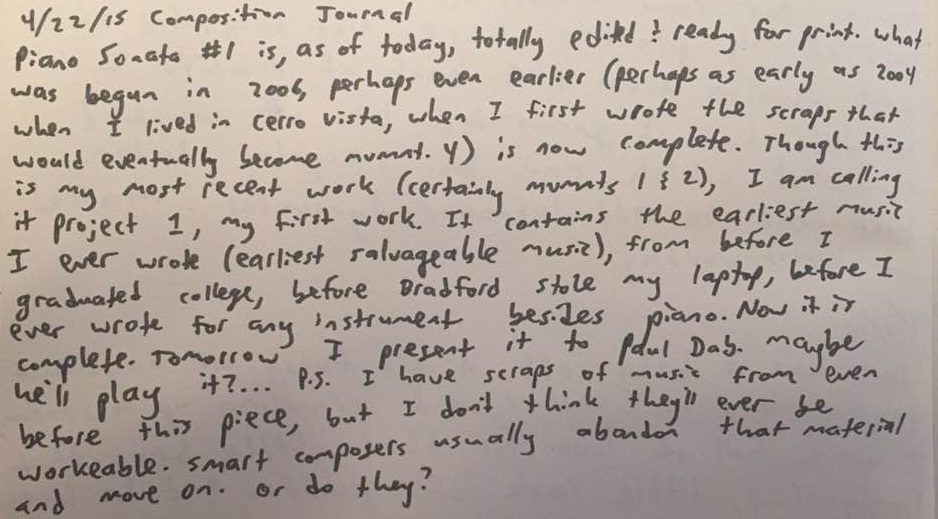

One of my favorite short stories of all time is “Quiquern” by Rudyard Kipling, from The Second Jungle Book. If you’ve never read the two Jungle Books, I highly recommend them. The Disney film only scratches a tiny surface compared to the epic stories by Kipling (Mowgli’s story is really only the first of like 20 stories). The writing is so crisp, and these stories do what all great sci-fi and fantasy stories do: they create an entire fully-formed world for the reader to explore. The world is rich and complex, and the lessons it teaches are piercing and difficult to shake.

The Disney film is fun and jazzy and hip and carefree; the written stories are raw and wild, filled with the brutal poetry of the jungle. The characters are bound by the laws of the jungle, the unwritten rules and shared understandings that guide every action the animals take. The laws dictate how to behave in times of drought, when and where hunting is permitted, and how to interact with the ever-expanding, dangerous world of Men. Only Mowgli is unbound by the laws of the jungle. Therefore he rules the jungle.

There are also so many hidden messages and deeper meanings packed into Kipling’s verse. Every story begins and ends with poems, the meanings of which change after reading each story. For example, this one:

And his own kind drive us away!

At first reading, it is a nice little poem. But after reading the story that follows it, “The Miracle Of Purun Bhagat,” the poem becomes so tragic and beautiful. Every story has these lovely little nuggets, and they make the reading experience so rich.

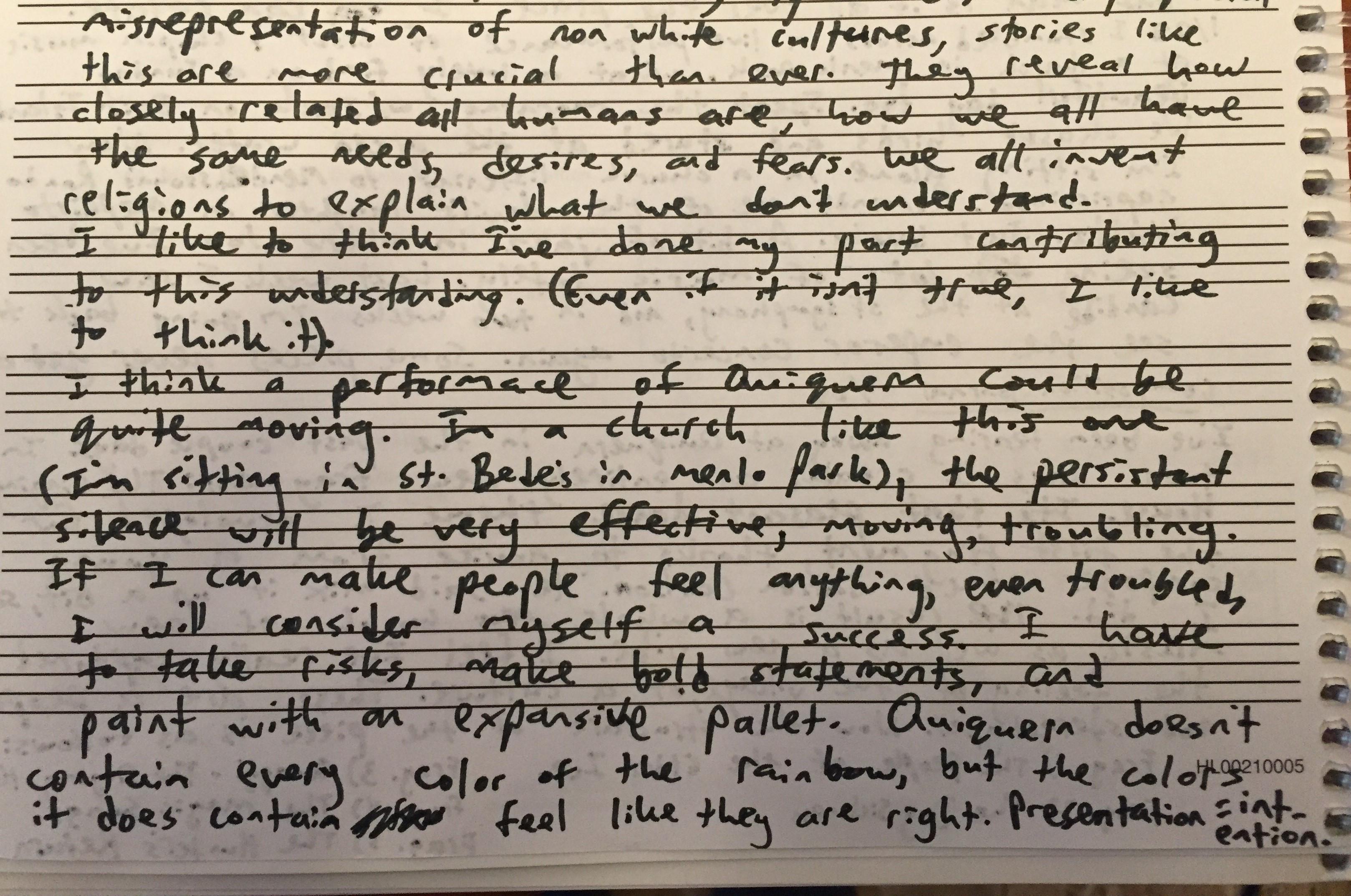

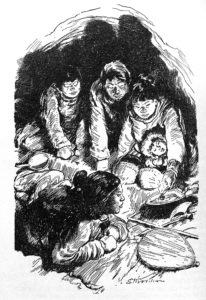

“Quiquern” is the story of a young Eskimo boy who lives in a tiny village surrounded by a frozen arctic wasteland. The village’s only source of food is seal meat which they catch with the help of their many well-trained dogs. One particular dog is born a runt, shrunken and sickly in the freezing wind. However the young boy cares for the dog, and raises him as a member of his own family. His love for the dog is pure and innocent, and together they frolic in the snow like siblings.

One year the winter is especially harsh, and the ice does not recede. The surplus seal meat runs out, and the people of the village soon begin to starve. In their moment of desperation they eat the wax from their candles, the leather from their belts. Their beloved sled dogs, still chained together in groups of eight, insane with hunger and fearing for their lives (just as lion cubs must fear their mother in times of hunger) break their chains and run screaming into the white waste. The people of the village become living skeletons.

The boy and a young girl from the village, still strong in their youth, announce to the village that they will venture out into the ice storm and find food for the village. It is suicide, but nobody stops them. Within days of their departure they are hopelessly lost, freezing, and beginning to hallucinate. They kneel shivering in the snow and announce to the heavens that they are man and wife. As darkness closes around them they pray to Quiquern, the eight-legged spider god of the arctic, for salvation and mercy.

The two children open their eyes to see a massive creature barreling toward them in the distance, eight legs scurrying effortlessly across the snow. A giant, hulking body becomes larger and larger in the morning haze. Quiquern has arrived to devour them; they are helpless as newborn seals. It is the end of their short lives, the end of their people. Two freezing, starving children prepare to die alone on a frozen plain at the edge of the world.

However as their eyes focus, they realize that the eight-legged creature is actually two dogs, running wildly through the snow pulling an empty dogsled. The dogs are well-fed and excited, blood dripping from their snouts. At the front of the pack is the runty dog the young boy once saved, frothing with joy at the sight of his oldest friend.

Carried by the sled dogs, the two Eskimos travel for miles to an open pit in the ice, where fat seals emerge for air. The dogs had found the hole in the ice and gorged themselves on meat. The boy and his wife fill the sled with food and return to the village as heroes. The village, now inhabited only by ghost-like creatures with sunken eyes, celebrates by burning whatever candles they have left. An ancient people go on.

This story burrowed down inside me and left its mark on my soul. I’m not sure why, I can’t explain it, but it filled me with the urge to write music. Originally I set out to write something eerie and cold and empty, three flutes crying out across the Arctic plain. But as I wrote, I realized it needed some bass, so I worked a piano into the mix. Years later, I switched out a flute for a clarinet to give it one more color, and that ensemble is the one that remains.

I’ve always loved my piece, Quiquern, just as I’ve always loved the story Quiquern. I can’t exactly say what it is that draws me to both, but drawn I am. Over the years I’ve written notes about this music in the margins of my journal: “Don’t forget, you love Quiquern. Don’t discard it.”

The artwork at the top of this post is by the very talented artist and sculptor Jenna Trost. Please visit http://jennatrost.com/ to see more of her lovely work.

The music you’ve been listening to is the completed first movement of this work, which is called “The People of the Elder Ice”. I hope you’ve enjoyed it. The entire middle section of this movement, which I refer to as “Village Dance,” was actually added later. Read about that addition here. For Part Two: “The Dog Sickness,”Click here.

San Rocco a Pilli

In the scorching heat of midday the villa was abandoned, deserted, post-apocalyptic. I hunted across the grounds, running my fingers through the golden Tuscan grass, snooping down dark hallways and looking out the ancient, cloudy windows that appeared to be made of clear honey, though they felt solid to the touch. I wandered into a giant barn. No farm equipment or hay, just faded wood panels and a colony of snoozing birds that had taken up residence in the rafters. The high ceiling and heavy, silent air reminded me of a cathedral; solemnly I knelt to inspect an old nail on the floor. Anxious to hear any type of sound, I lightly rapped the rusted door with my shoe, and the birds suddenly took flight in a panic of feathers and chaotic squawking, swooping down savagely at the invader, filling the previously silent space with noise and anger. I covered my face, perhaps in shame at how thoroughly I had destroyed something so serene, and ducked out the door into the burning sunlight, leaving the birds to return to their prayers. The hot, fallow fields and gentle hills in the distance looked on, unphased and without judgement.

A single gust of breeze meandered past the sweat on my neck, providing just the faintest hint of cool. I breathed deeply, filling my lungs with the air my ancestors breathed so many hundreds of years ago, when the villa at San Rocco was a powerful fortress guarding the countryside, a pillar of strength. Today the villa still stands a lonely guard upon its abandoned hill, but it’s empty and choked with native weeds, its only occupants birds who sing lustily from the treetops and build their nests in the red roof tiles. The outer walls of the buildings all have loops for tying up horses, but there are no horses that need tying up, and rusted farm equipment sits neatly in a line along the field’s edge, more as a creepy decoration than as tools ready for hard use. I dunked my head in a pool of cool water, and hid from the sun in a cobwebbed vestibule that no doubt once offered shade to a 17th century farmhand after a long day’s work. Sitting against a post in the shade, I began to dose. Two tiny birds flew in to get some shade and woke me from my brief nap, but upon seeing me there they departed in disgust. Wrapped tightly in the silence of the afternoon, I let my mind wander the fields.

Why do I find myself feeling jealous of these happy Tuscan birds? As I drift across the countryside searching for something that will lend meaning to my life, these small creatures are content to lay in the sun, to cool their feathers in a pond, to sleep the day away in the rafters of an old barn. Life seems to have purpose and no purpose all at the same time. One day I will disappear and be forgotten, perhaps as if I never existed, much like my ancestors who lived in Italy for hundreds of years, of whom no record exists, whose lives have been utterly forgotten by posterity, entire lives full of laughter and sadness and sex and longing and glorious moments and religion and debate and watching the sun set in the hills and babies born and tragedy and art, erased and forgotten; just as the two birds who flew into my vestibule might never have existed at all, and perhaps lived only in a dream, a dream which I am already beginning to forget. I’m sorry little birds! I don’t want to forget you. I want you to live forever, wild and free in the Tuscan sun. But if you must be forgotten, I want you to live your lives with reckless happy abandon. I want you to drink the air with hearty gulps and dance in the breeze and dive like missiles. I want to join you. Then we can be forgotten together, but we won’t care because we will be birds, smooth and fast, and we’ll make our nests in the tiled roofs of old villas.

Back inside the cool, dusky main house I glimpsed the curvy figure of a piano tucked away in the darkness. The instrument called my name, beckoned me seductively. I approached in a trance. Staring transfixed at the candlestick holders bolted to the wooden frame, I reached desperately for her smooth, white keys. But sadly when she finally felt my tender caress, she could only respond with the dull creak of decrepit age. Dust choked the arteries that once pumped sweet music down these old halls. The piano and I wept together as two lovers who have irreconcilably grown apart. I did not touch her again.

I wandered down a hallway filled with ghosts. A laughing cavalier smirked at me as I tried a locked door. Though the sun still boomed through the open window, the hallway grew more ominous as I crept down toward the dead end. This hall was different from the others, more silent, more deserted, painted differently – as if the craftsman rushed to complete his job and be away from this place. I felt something slide under my skin, an urgency, the instinct to flee. These old ghosts are not scared of the burning noon sun. They are Romans and Tuscans and hard men, and they can smell the softness of my pampered hands, the hands of an untried and cocky young man who fancies himself an adventurer. They mock and beckon. Feeling their presence, I fled in shame and with much haste. Put me on a train back to Rome, get me out of San Rocco, before I join the ghosts and become another smirking face in some faded painting, inviting naive tourists down well-lit hallways that reek of death and lead paint.

Somewhere among the dusty back-trails of Eastern Idaho, an old forgotten wagon road bakes in the sun. The prairie desperately wants to swallow it up, to make it disappear forever, just as the people who made this road have disappeared. Yet despite the countless rainstorms that year after year wash away the top soil, and the cattle herds that trample the ground into brown paste, and the prairie winds that threaten to bury this holy place in sediment, the road endures. It cuts across the frontier in a searing straight line, as if the land itself was branded with hot metal. Its rivets are clear and stark in the afternoon heat.

It was at this spot that thousands and thousands of pioneers, adventurers, families, wanderers, refugees, entrepreneurs, and thrill-seekers carved their names one by one into the earth, until all the names ran together and all that remained was an ungainly scar. A mighty river of people once flowed here, people willing to take bold action, people with new ideas. These people made the West, or at least changed it drastically. They are all gone now, their names and faces long forgotten, the names and faces of their children forgotten as well. But their road remains. An accident of history, the byproduct of something much greater than itself, yet it outlived them all. From the looks of it, this old road will be around for a long time to come.

I wish you all the best Old Road. And safe travels to any who may tread on you. May you once again serve a higher purpose. You were a good old soldier, and perhaps your best days are behind you, but there’s still a job for you, still a chance for your time here to have some meaning. Sure most days you’ll go completely unnoticed. None of the travelers who trampled on you will come back to honor you for the role you played in their lives, in our history. Alone in the wilderness, forgotten by the world, you long to be useful again. Old Road, today you were useful. You were necessary. You were exactly what I needed you to be: a quiet spot for a tired, windswept tourist to stare at the burnt grass and think longingly about the past.

So you want to “work on music stuff” and feel like a productive artist, but you also want to watch Game of Thrones, drink a beer, and chill. How to balance all of this? How to make progress on creative work when you’re not feeling at all creative? Answer: create parts!

Creating parts is tedious work, but necessary if a piece is ever to be played by an ensemble. The work can be done almost anywhere: on the go, with children running at one’s feet, while watching Joffrey die at his own wedding. So if in the evening I am feeling lazy and uncreative after a long day at work, I whip out some parts and chip away.

I’ve got a somewhat efficient process for it. It mostly involves making tiny changes to the spacing to ensure that nothing bumps into anything, and creating logical page turns so the musicians don’t think I’m a total noob. Sometimes this makes the spacing a bit crammed, but it makes for a more professional product.

Though there’s not a lot of magic in the process, I always feel good that I accomplished something when I finish creating parts. I have to be honest with myself though; I know I’m partly doing it to avoid the truly challenging work of creating new music. I haven’t really written something new in a while. I was working on the Polish piece for a long time, but getting nowhere, spinning my wheels, generating lots and lots of new ideas with no real plan for how they should fit together (a practice Schoenberg openly criticized). When I get stuck in such a rut, I usually turn to part creation to avoid the hard decisions I need to make about a new piece. When trying to finish a piece that has too many ideas, some ideas need to be cut and discarded. But when I’ve spent too much time “inside” a piece of music, I end up falling in love with every possible version of it. Brainstorming has its place in the creative process, but when brainstorming becomes the entire process, nothing ever gets finished.

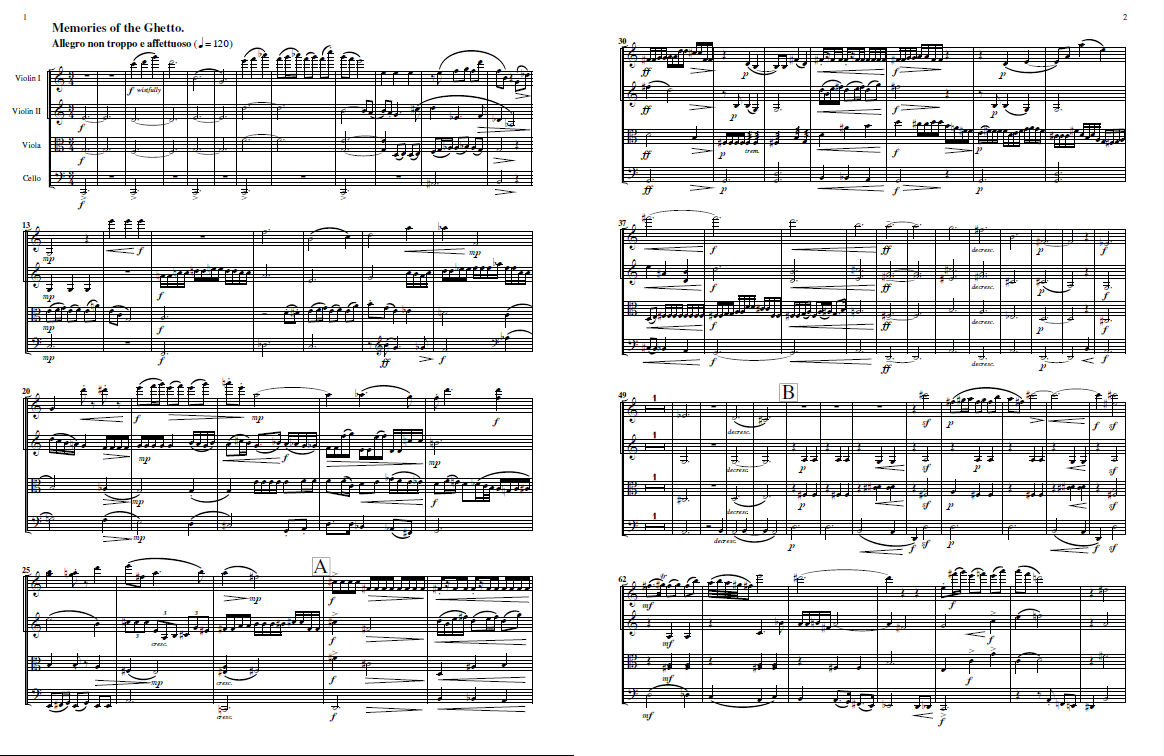

So I’m creating parts today. I’m currently working on the parts for my string quartet (Jackdaw). It’s a piece I have always loved, very nostalgic and at times quite sad. A deep sense of longing runs through the entire work. It’s about a lot of things, but mostly my own Jewishness, my desire to feel connected to my own ancestors, their own struggle fleeing persecution and what they left behind, a way of life that is gone forever. It’s also about Kafka.

Here’s the music:

Working on this piece again makes me feel connected to it even though it is long completed. It helps me feel like an artist to be reminded that I am capable of completing work and still loving it years later. Maybe this process will even help me get back to work on the real matter at hand: writing something new.