“Democracy for the vast majority of the people, and suppression by force, i.e., exclusion from democracy, of the exploiters and oppressors of the people–this is the change democracy undergoes during the transition from capitalism to communism. Only in communist society, when the resistance of the capitalists have disappeared, when there are no classes (i.e., when there is no distinction between the members of society as regards their relation to the social means of production), only then ‘the state… ceases to exist’, and ‘it becomes possible to speak of freedom’. Only then will a truly complete democracy become possible and be realized, a democracy without any exceptions whatever.”

Vladimir Lenin, The State and Revolution, Ch. 5 part 2

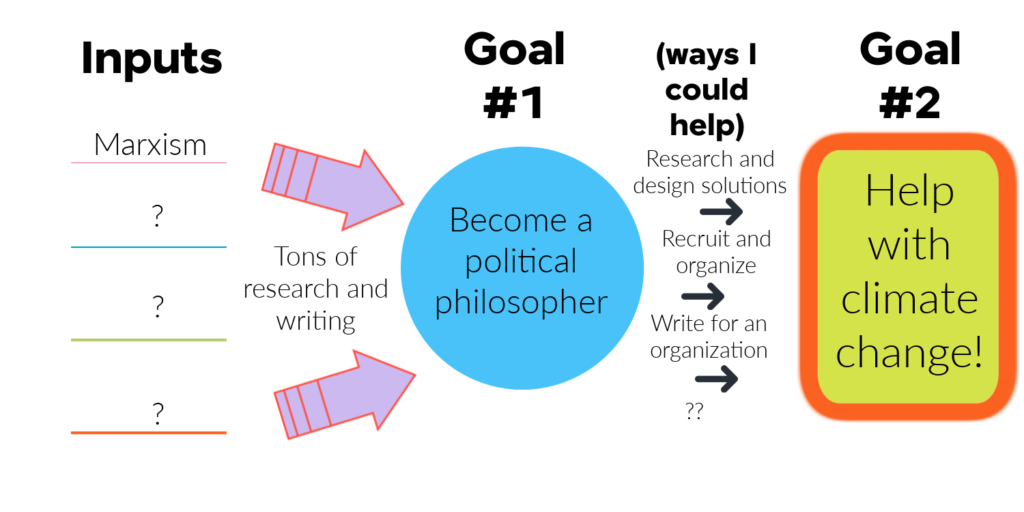

The quote above does not sit right with me. I’ve been developing a hunch, or perhaps it’s better to call it a question: can democracy ever realistically thrive under a communist regime? Lenin, quoted above, promises that communism and democracy will support and reenforce one another, that both will thrive together. He argues that by limiting democracy (disenfranchising the “oppressors”) we can eventually create a fuller democracy than any the world has yet seen. But I remain skeptical that a fuller democracy can ever realistically blossom within a communist society, despite Lenin’s promises. Lately I’ve been reading Lenin (State and Revolution and What is to be Done), Trotsky (History of the Russian Revolution), Richard Pipes (The Russian Revolution), Kolakowski (Main Currents of Marxism), Karl Popper (The Open Society and its Enemies), and some Plato too. These writers have greatly influenced my thoughts on this subject. Here’s the way I see it at this moment:

Lenin (and Marx to a certain extent) promise that the coming era of communism will usher in a much more complete democracy than what is possible under capitalism. Yet in order to reach that goal, Lenin openly argues that democracy (for the exploiters and oppressors, and their allies) will need to be curtailed. This appears to be a strange and contradictory argument: we can only expand democracy by limiting it. Personally I get stuck on this point, even if I agree with much of Marx’s critique of capitalism. Lenin’s reasoning sounds so much like some Orwellian parody of totalitarian logic (we can only have freedom if we all become slaves, we can only eliminate the state if we usher in a dictatorship), that my mind struggles to accept its validity. Something here isn’t right.

How can we expect democracy to expand if the first step toward expanding it is the disenfranchisement of “the exploiters”? Afterall, who are these “exploiters?” Such a vague and malleable term, easily abused and manipulated in the hands of a revolutionary tribunal. We must go even further than asking how we will define exploiter, and ask who will decide the definition? This is not a semantic question; the answer to my question will determine who loses their right to participate in this so-called expanded democracy. It’s easy to picture the exploiters as some small cohort of Wall St. fat cats and billionaires, the top echelon of the 1%. To Lenin, these are obviously the “bad guys,” those most responsible for income inequality and exploitation, the first on Lenin’s list of citizens to be purged from the voter rolls (perhaps purged from life itself). But I think any revolutionary party would find that many, many more people than just the top 1% will need to be disenfranchised before the revolution can proceed.

So who is to be robbed of political power? I think the answer would turn out to be: whoever stands in the way of the revolutionary party’s agenda. Realistically, it wouldn’t only be the top tier capitalists who stand in the way of revolution, but also the millions of citizens who align philosophically and ideologically with conservatism, i.e. anyone who believes we should not overthrow capitalism, any one who values the concept of private property. Lenin’s program is so extreme, many left-leaning liberals (who might, in different circumstances, support a progressive government) would flock to conservatism’s banners if private property itself (the concept) was threatened. If democracy were allowed, Lenin’s agenda would face serious, united opposition. To complicate things further, a significant portion of these dissenters would likely be workers.

How can a revolutionary party tolerate these dissenters, if the primary goal is to instigate revolution? I believe the revolutionaries would feel the need to persecute these conservatives regardless of their class status, meaning that working class conservatives (many of whom would certainly resist a communist revolution) would need to be disenfranchised, despite their proletarian status. Whether or not these people are correct for opposing revolution is beyond the scope of this essay. All I mean to say here is that not only the “fat cats” will be disenfranchised, but also many lower-class proletarians as well. This truth uncovers a flaw in Lenin’s materialist logic: economic forces cannot be the sole driver of human action if so many proletarians oppose communist policies. In the real world, it forced Lenin to admit (through his actions) that this corollary is true: Lenin and his Bolshevik Party did not actually fight for benefit of the working class; instead they fought only for the benefit of those who ideologically agreed with Lenin’s philosophy and Bolshevik policies. Essentially Lenin was offered a choice that amounts to the ultimate test of his philosophical integrity: a) allow all proletarians to vote on government policy, thereby sacrificing his communist dream at the altar of proletarian democracy, or b) hold onto power all costs, which entails labelling all dissenting proletarians as class traitors and terrorizing/purging them via a network of informants, secret police, and concentration camps. Of course he chose B, and set the stage for Stalin’s later perfection of the method.

What else could Lenin mean by “exploiters and oppressors” besides those who oppose the revolution? If a large bloc of proletarian conservatives stood in the way of revolution, Lenin would either be forced to purge them from the revolutionary party, or accept that when these citizens vote they will vote against communism, which will likely doom the whole revolutionary effort. Lenin imagined in his pre-revolution writings that it would be easy to identify who deserves to be purged (basically all non-proletarians). In other words, he had a failure of imagination when picturing in his mind his beloved proletariat (or perhaps he idealized them). Either way, he failed to notice that many, many proletarians opposed the Bolsheviks. Thus upon his assumption of power in Russia, he was faced with an unexpected backlash from his own constituency.

And so, predictably, he purged dissident workers right alongside dissenters from other classes. This embarrassingly reveals that class is actually not the most important defining category for Lenin; what he actually cares about even more than class is orthodox agreement with his own political views. Any who can’t meet that standard must be disenfranchised – regardless of class – otherwise the revolution will fail. So the revolution cannot proceed without massive disenfranchisement across all the classes, a disenfranchisement based solely on political beliefs, not on class status.

Thus the quote at the top of this article is proven false. Under Lenin’s revolutionary program, classes do not disappear. The new ruling elite are not proletarians as Lenin promised, but Party Men. One’s class status is determined by one’s obedience to the government and affiliation with the party that rules it. The quote above is also false in its assertion that a truly complete democracy can be realized under (Lenin’s) communism. Lenin’s program can only be implemented if all who disagree with it are labelled as “oppressors” and disenfranchised. How could the disenfranchisement of all citizens who hold ideas contrary to those of the ruling revolutionary party really be the first logical step toward expanding democracy? And how can Lenin claim to rank proletarian status as the ultimate defining feature of his ideal citizen if he does not have a plan for how to deal with proletarians who disagree with him?

If we assume, as Lenin did, that all proletarians will unanimously agree with Leninism, then the question of whether or not to purge proletarians who disagree with Leninism becomes a non-issue. But by doing so, we imagine a world that does not exist today and, given the realities of life in a pluralistic world, is unlikely ever to occur. Though that doesn’t stop utopian thinkers like Lenin from imagining that the proletariat is capable, as if they were one singular body, of absolute unity of thought and purpose, of hive-mind behavior. Perhaps if economic and social circumstances in the USA degraded to such a horrendous extent (as they had in Russia during WWI and after the February Revolution) that a majority of Americans were going on strike, marching in the streets, and demanding urgent and dramatic changes, then Leninist parties might be able to claim large-scale buy-in by the workers. But even then, there would still be workers who believe that parliamentary democracy is the most feasible solution to the country’s problems, and many others who rally to right-wing banners, and many others that would consider themselves progressive while refusing to reject the concept of private property (these types also reject the Bolshevik’s violent methods in favor of constitutional, legislative reforms). This was all true of the Russian proletariat in 1917. In other words, the only way to assume that Lenin wouldn’t need to fight against, disenfranchise, silence, and persecute members of the working class is to assume that all members of this enormous and diverse class are capable of rejecting all but one economic-political theory, of fighting for one singular economic goal (at the expense of all other goals). Humanity doesn’t work like that, not ever.

Pluralism in political thought must be acknowledged by any political theory who wishes to do more than construct utopias in his mind. There are countless reasons why many proletarians, despite sharing with the Bolsheviks a sincere desire to improve the lives of the poor, would reject Leninism entirely. Many proletarians are religious people who might fear losing their freedom to worship, while many others are parents who may oppose revolution simply for the sake of maintaining a peaceful world for their children, while others are patriots who would remain loyal to their countries and therefore oppose an international communist revolution, and others still are modern constitution-loving liberals who consider incremental change to be the ideal way to reform capitalism. Turns out there are many reasons why a proletarian might oppose revolution, and many reasons why their class status might not be the most important motivator behind their ethical and political decisions.

Lenin assumes in a cavalier fashion that the dissenters will be a tiny minority, and all of them complicit in the evil doings of capitalism (i.e. they’re bad guys, and there aren’t a lot of them, so we don’t need to feel bad purging them. In fact, once we purge them, we can finally have the communist society that we, the good guys, all secretly long for). And so when Lenin claims that class status is the most important defining factor in a human’s life, the factor that determines one’s inner-most desires, the factor that determines whether one gets a voice in the new society, he is constructing an “ideal” version of the proletariat, a perfect version. When Lenin discovered that this ideal proletariat did not really exist, he determined that must never allow democracy to fall into the hands of the workers.

So either:

- Proletarian status matters more than anything else, in which case the revolutionaries would need to allow proletarian dissenters (conservatives and liberals) to vote, and Lenin’s vision of revolution will likely fail, since class status does not directly determine one’s political beliefs, and the whole body of workers hold so many conflicting opinion about economics, revolution, democracy, politics, religion, etc.;

- Or orthodox adherence to the revolutionary party’s goals matter most, which will mean Lenin will be forced to disenfranchise many proletarians, which will reveal the lie behind Lenin’s claim that under communism democracy will be in the hands of proletarians – in fact it will actually be in the hands only of those who agree with Lenin.

Neither scenario gives us a situation where a communist revolution ushers in fuller democracy, or for that matter a democracy in the hands of the proletariat.

I don’t think Lenin would be ready to admit that he ranks “orthodox acceptance of his ideals” higher in importance than class status. He avoids facing this question by instead simply believing that all proletarians are capable of relentlessly pursuing the same political and economic goals; any who oppose these goals must necessarily be in a different class (the oppressive classes), or are perhaps just brainwashed puppets of the oppressive classes (and so must be purged for the common good). True proletarians are incapable of supporting capitalism, representative democracy, or incremental reform on their merits alone. So any proletarians who do support these things must not be true proletarians. In this way Lenin can claim to rank class status first in importance: he defines one’s class not according to one’s material conditions but according to whether that person agrees with Lenin’s views. One simply cannot be a proletarian unless one agrees with Lenin.

I don’t believe all of this was conscious for Lenin; he really does seem to believe that “true proletarians” will all support his personal political goals. Like a Platonic idealist, Lenin appears to believe in a sort of divine category called “proletarian.” All who fall into this category share the same goals, beliefs, desires, and dreams. If given the opportunity, they will prioritize the needs of their class above all other priorities, including religious, familial, national, and of course political. All we need to do is cleanse society of the poisonous residue of capitalism, and the true proletarians can finally come together and achieve their full communist potential. Therefore, according to this idealist-Marxist logic, the proletarians will never fight amongst themselves or disenfranchise one another because they will all agree on the efficacy of disenfranchising the oppressors (and it will be obvious who those people are). The elimination of inequality, exploitation, and profit-motive is the dream of every hard-working proletarian. In fact, Lenin extends this “theory of forms” to all the classes: not just proletarians but also capitalists and middle class people all think a certain way. They are predictable in their ideologies and desires, likely to act a certain way according to their class status. Therefore a figure like Lenin, who can see into everyone’s minds and hearts with the clarity of a god (much like Plato’s philosopher kings who alone understand the nature of the divine Forms), can steer large populations of people according to his almost divine will, and shape society along those hard and unbreakable class divisions.

Or so Lenin might have imagined it.

And then beyond that, I struggle with the question of how, assuming a communist society is able to survive this dictatorial phase of the revolution, democracy can be maintained under communism. Remember, Lenin openly admits that democracy will be curtailed to a certain extent during the revolution, but the second part of his prophesy is that after the revolution, once communism is established, democracy will expand to an even greater level than was possible before the revolution (this promise is made throughout State and Revolution). So Lenin’s promise for post-revolutionary democracy is even grander than his promise about the revolutionary proletariat persecuting the exploiters: he promises that communism will allow us to build “a democracy without any exceptions whatever.” But my intuition tells me that Lenin’s party-driven communism can only thrive if democracy is limited for good, and that the promise of an expanded democracy under communism is a misguided promise that can never be fulfilled.

Democracy cannot expand under communism because that would allow those opposed to communism to dismantle it, simply by exercising their right to vote (or voting representatives into office who will oppose communism). And even after the revolution, when capitalism has been dismantled and relegated to the dustbin of history (assuming it is even possible to do so), there will still always be citizens who wish to try new things, innovate, and challenge the ruling cultural and governmental paradigm. This will be true even if (especially if) communism is in place. Voters who wish to experiment with capitalism, question whether communism is the best method for running an economy, or desire the freedom to practice profit-seeking activities, might vote for policies that undermine communism. And since communism can only be maintained if capitalism is absolutely disallowed from seeping into the system, this sort of “chipping away” would destroy the entire communist effort. Only by purging from the voter rolls those who dissent can communism be maintained (or by disallowing voting altogether, as so many actual communist regimes have done). This of course can be done, but it certainly will not lead to an expansion of democracy. In fact, if this democracy can only allow those who agree with the communist party to vote, this really isn’t a democracy at all; it’s single party rule.

Entropy is the enemy of communism. Communism can only be maintained if the society is united in favor of it, or if those who oppose it are disenfranchised and prevented from practicing capitalism. Every time a free market is allowed to blossom under the communist regime, it weakens communism. But experimentation and profit seeking seem to be natural human behaviors. In any society there will be those who wish to challenge authority, experiment with activities that are banned, or simply try new things. Sometimes these behaviors are driven by profit-motive, but other times those who undertake these risks do so despite the fact that even if they succeed there will be little personal gain (picture Galileo experimenting with physics under the watchful gaze of the authoritarian Catholic church). No matter what social, cultural, or economic system is installed, there will always be humans ready to challenge it. Therefore communists will constantly need to fight entropy to maintain the communist vacuum (i.e. they will constantly need to prevent anyone with ideas that oppose or undermine communism from practicing or voicing those ideas, or voting at all in the “expanded” democracy). Only by eliminating dissenters can communism be maintained, as dissent only introduces cracks and flaws into the system. But if it can only be maintained by purging dissenters and maintaining single party rule, that means democracy is opposed to communism.

The communist tribunal in charge of determining who will be disenfranchised will have some tough questions to wrestle with: shall we allow free-thinkers to speak and act as they please, even if their ideas might undermine communism? Should we allow their ideas into the public forum, where others might debate the ideas or even build upon them? Or do we need to follow Plato (in The Republic) and ban dangerous ideas in order to maintain the purity of the people (to keep people in their ideal categories)? Do we need to disenfranchise or purge any who seem naturally inclined toward profit seeking? Or do we allow any and all to vote, even if the citizenry votes for economic liberalism? How can communism be preserved if regular citizens are allowed to question it, to convince others that it is worthwhile, to allow more income-inequality into society for the sake of upward mobility and innovation, and to accrue wealth and speak publicly about the merits of the profit motive? Either democracy or communism will need to give way.

Perhaps, one could argue, experimentation of this sort is not part of human nature and that it can be expunged if we change the cultural and material forces, if we engineer an ideal society. Perhaps under communism the people will be so content and well-fed, so fulfilled and self-actualized, so full of species-essence, that there will be no need to experiment with the profit motive ever again. All members of society can live their lives in peace, blissfully content with the eternal and unchanging status quo (and so communism would make conservatives of us all). Again, this is just Platonic thought lurking behind the facade of Marxism: the citizens of the ideal polis will all be perfectly content in their categories for all time; the polis will provide all citizens with everything they need to thrive and to fulfill their respective roles in the collective. Who in his right mind would fight or even dissent against the ideal polis (except perhaps one of those nasty exploiters we discussed earlier, but they’re all gone now). Ah Plato, that great enemy of democracy, shows up in the strangest places. Lenin promises democracy, but secretly, quietly, he whispers: why do we even need democracy, since under communism everyone will agree? And so communism will be Lenin’s ideal polis, where justice will be defined as a man fulfilling his role in society without complaint, and where innovation will become unnecessary because perfection has already been achieved. We can even do away with voting because unanimous consent among the entire citizenry will reign. Once communism is established we can arrest all change. There will be no dissent, so there will be no need of democracy or the state. We will all live like brothers and sisters, just as Plato’s guardians would live, if they truly all believed they were gold-souled.

So during the revolution we will need to limit democracy in order to dethrone the bad guys. Then after the revolution, democracy will only be granted to those who agree with the ruling party. Lenin believes this will be just about everyone who is left. Because he believes this, he prophesies that democracy and the state itself will wither away since there will be no need of them (who needs a state, or voting, or politics for that matter, if we all live in eternal peace, agreement, and brotherhood). It’s obvious by now that I consider this prophesy to be an overly optimistic statement of faith. All dissenters will lose their rights to vote (or their lives), and only through severe limitation of the electorate can Lenin be proven true: all voting citizens will agree that communism is the best and most glorious goal for society to pursue because in the end only party members are allowed to vote (and even party members can be easily purged if they disagree with the head man). Or to put it another way: kill everyone who disagrees with us, and we can finally live in a world where everyone agrees on everything (or pretends to agree, out of fear of the purge).

I don’t claim to know the hearts and minds of other men and women. All I can really know is my own mind, and even that can be slippery. So I’m not trying to build some grand theory about human nature. This essay is about the insolubility of democracy in a communist society. I do not consider this question solved for me, nor is my mind made up. In fact I am eager to be convinced otherwise! I ask: can we establish a society with more social and economic equality AND expanded democracy? More work to be done on this front. I’ll note that I do not wish to assassinate Marxism at this time, but only Lenin’s claims about democracy. I hold Marx’s critique of capitalism in the highest regard; he cuts right to the core of what is wrong with capitalism (just as Plato did to democracy). But though Plato, Marx, and Lenin were all expert critics, their proposed solutions were extreme and far-fetched, so I challenge them. Despite their genius and the raw power of their analyses, I challenge them. I reject the parts of their philosophies that endanger democracy, even if I fear where capitalism is taking us. If anything I want to distill the best and most useful parts of Marxism (not so much Platonism), and discover ways to apply those Marxist ideas today, to contribute toward solutions to the pressing problems of our time. But I fear the uncertainty, danger, and authoritarianism of open revolution, and I do not wish to throw democracy in the trash can in the name of overly optimistic experimentation. I worry that Marxism creates too slippery a slope toward authoritarianism.

I should note that I am writing this in the USA, where we currently have a representative democracy. Flawed as it is, it is still a democratic state, which sets a high bar for any revolutionary party hoping to overthrow the current system. Whatever new system they establish would need to include more and better democracy than what we have now, otherwise it will be tough to recruit enough Americans (liberty-minded and democracy-loving as they are) to join the revolution. If I was instead writing from a country with little or no legitimate democracy, or a country still mired in feudalism or facing widespread famine and deprivation or crushed under an imperialist regime, then perhaps the Leninist proposal would carry more wide-spread appeal. Afterall, any democracy would be better than none, and at least the Leninists promise some democracy. But if Marxists can’t find a revolutionary model that appeals to Americans (which will likely mean maintaining high levels of liberty and democracy), then they guarantee that the American people will fight valiantly against the revolution. So either democracy, economics, politics, and culture have to degrade considerably in the USA, or Leninists need to come up with a plan that actually appeals to citizens in a modern democracy, otherwise Leninism is a dead-end in America (and the entire western world I’d wager). Or perhaps Lenin would argue that all citizens of modern-day America are “oppressors” who deserve to be purged by the world-wide proletariat. He might get some support for that one.

Addendum: Review of Karl Kautsky’s Dictatorship of the Proletariat:

Kautsky buys into the Leninist idea that socialist transformation is inevitable. But unlike Lenin he emphasizes (in a somewhat convoluted fashion) that socialism cannot exist without democracy. Lenin was eager to abandon democracy the very moment his party seized power, and this is really the basis of Kautsky’s scathing critique of Lenin’s tactics.

In his own way, Kautsky supports bourgeoisie democracy because it lays the groundwork for (what he perceives to be) the inevitable proletarian revolution, and allows the workers to voice their grievances and form workers parties (capitalism generally comes with liberty and freedom of speech). He believes that if capitalism continues to grow, the disenfranchised proletariat must grow with it, and so capitalism will inevitably create communism, as Marx argued. The working poor will grossly outnumber the wealthy, and so they will eventually vote their way into power. Kautsky assumes that the workers in a democracy, once given the power, will unanimously demand socialism. And so he’s not so different from Lenin, in that he believes that class interest motivates all decisions (also known as vulgar materialism). Like Lenin he has an idealistic image of a united working class all sharing the same demands and motivations, without disagreements or deviations within the ranks. This is not how real politics works, which makes the idealism of Kautsky and Lenin appear particularly quaint (and in Lenin’s case, dangerously naive). Though Lenin and Kautsky subscribe to the same brand of idealism, they disagree on the timeframe: Kautsky prefers the slow and even development of socialism over time; Lenin demands a violent and immediate revolution (any who refuse to come along with his plan must be purged).

So Kautsky and Lenin both share the same end goal, only that Lenin was too hasty to get there. What is really at the heart of this disagreement over the timeframe of the revolution is a more critical disagreement about democracy. Democracy is a crucial feature in Kautsky’s imagined revolution, and in his imagined communist society that follows that revolution. To take it even further, Kautsky believes that socialism cannot exist without democracy. Without democracy the whole plan will decay into dictatorship. In this regard he was proven right by Lenin. The Bolsheviks’ first move was the dismantling of democracy, including democracy among the workers (many of whom dissented or belonged to different parties from the Bolsheviks). By the time the Bolshevik transition to power was complete, real socialism (read: equality between all classes) was dead in Russia: Lenin’s party (read: the new ruling class) controlled all facets of government, culture, and society, while the teeming masses were disenfranchised, impoverished, and completely unable to openly voice grievances. The Bolsheviks’ so-called “dictatorship of the proletariat” was just a dictatorship, not socialism.

So Kautsky is right in the sense that socialism without democracy decays rapidly into dictatorship or single party rule. However Katusky isn’t particularly clear about how democracy will inevitably lead to socialism. While Lenin squashed democracy in order to preserve his party’s power, Kautsky sees democracy as the pathway to real socialism. But this will only happen if the vast majority demand socialism, and agree on what “socialism” should mean. Lenin rightly understood that this isn’t really feasible. The democratic electorate simply cannot come together on such a large and ambiguous goal, if all citizens are allowed to vote and speak freely. And so Lenin and his small cohort of true believers staged a sudden coup rather than allowing the masses to vote him into (which he knew they would never do), and then once in charge he destroyed all vestiges of democracy in his rise to absolute power. Was this a cynical attempt to hold onto power, or did he truly believe that by eliminating democracy he would one day create real socialism? Answer: who cares. His method led to totalitarianism, so it was wrong. It was the wrong method both for creating socialism and for governing in general (call me a consequentialist if you like).

Lenin understood, unlike Kautsky, that democracy is more likely to kill socialism than birth it, because factions within workers parties and disagreements between large swaths of the population create deadlock and stalemate and thin margins for change. Generally the most revolutionary outcomes a democracy can hope for are the sort of liberal, incremental, compromise-focused changes that we typically see in parliamentary governments. Kautsky ignores the reality of pluralism: people hold different opinions and see the world through unique lenses, and this is true even within workers parties and unions. This is a natural facet of humanity, and cannot be ignored. It is a fantasy to imagine that something as intricate as a socialist economy could ever be democratically planned and administered, or that the entire population could even be made to agree that socialism is the correct path, or even be made to agree on one single definition of socialism. Democracy is far too messy and inefficient and factional for that. There will always be disagreement and innovation and challenges to the status quo, and economic factors alone will never be the sole driver of human behavior. This is why democracy does work well with capitalism, which is also sloppy and unplanned and competitive. Pluralism is one of the driving forces of capitalism, which (like the gene pool) is strengthened by diversity. Lenin understood all of this well, and so (as a hater of diversity) sought to prevent any who opposed him from exercising any democratic power whatsoever. Lenin couldn’t allow factions or even small disagreements to flourish within the party, so he dictated to the party members (and therefore to the people of Russia) exactly what they needed to believe. The result certainly was not capitalism, but it also certainly was not socialism.

So allowing real democracy is unlikely to lead to socialism, but snuffing out democracy only leads to dictatorship and totalitarianism. Socialism fails when it’s undemocratic, and it fails when it’s democratic. I fear that the message here is that socialism is impossible.