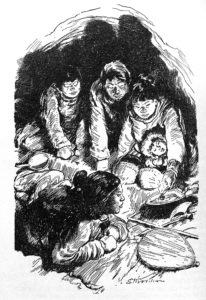

Quiquern is a five movement piece of music for piano, two flutes, and a clarinet, based on a short story by Rudyard Kipling.

Here is the story behind the music .Quiquern: The Magic Songs and Hunter’s Return

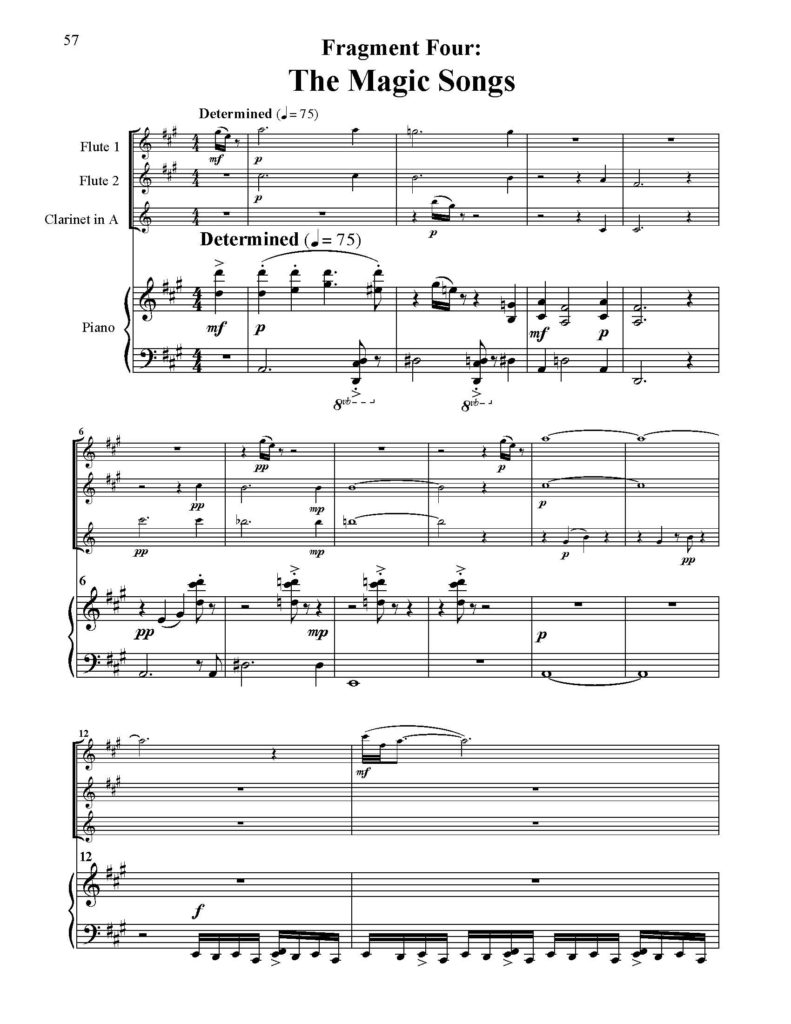

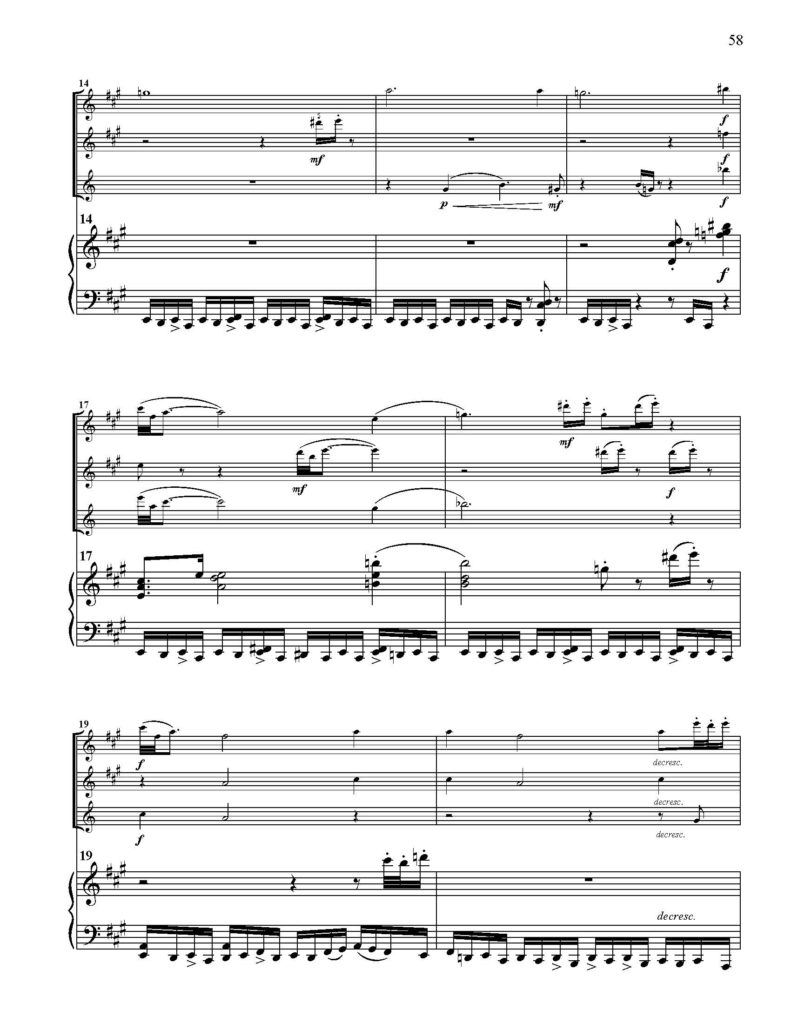

This next fragment of Quiquern is called “The Magic Songs”. Famished and delirious, Young Kotuko and the girl set out alone into the blizzard to find food for the starving village. As the dark and the cold and hunger devour them, the two children rave and hallucinate, unhinging themselves from the realm of men and into the realm of gods. As they descend, they sing songs of magic, songs buried deep in their memories, in their blood. Their voices rise and fall with the frozen wind.

And through this silence and through this waste, where the sudden lights flapped and went out again, the sleigh and the two that pulled it crawled like things in a nightmare — a nightmare of the end of the world at the end of the world.

The girl was always very silent, but Kotuko muttered to himself and broke out into songs he had learned in the Singing–House — summer songs, and reindeer and salmon songs — all horribly out of place at that season. He would declare that he heard the tornaq growling to him, and would run wildly up a hummock, tossing his arms and speaking in loud, threatening tones. To tell the truth, Kotuko was very nearly crazy for the time being; but the girl was sure that he was being guided by his guardian spirit, and that everything would come right. She was not surprised, therefore, when at the end of the fourth march Kotuko, whose eyes were burning like fire-balls in his head, told her that his tornaq was following them across the snow in the shape of a two-headed dog. The girl looked where Kotuko pointed, and something seemed to slip into a ravine. It was certainly not human, but everybody knew that the tornait preferred to appear in the shape of bear and seal, and such like.

It might have been the Ten-legged White Spirit–Bear himself, or it might have been anything, for Kotuko and the girl were so starved that their eyes were untrustworthy. They had trapped nothing, and seen no trace of game since they had left the village; their food would not hold out for another week, and there was a gale coming. A Polar storm can blow for ten days without a break, and all that while it is certain death to be abroad. Kotuko laid up a snow-house large enough to take in the hand-sleigh (never be separated from your meat), and while he was shaping the last irregular block of ice that makes the key-stone of the roof, he saw a Thing looking at him from a little cliff of ice half a mile away. The air was hazy, and the Thing seemed to be forty feet long and ten feet high, with twenty feet of tail and a shape that quivered all along the outlines. The girl saw it too, but instead of crying aloud with terror, said quietly, “That is Quiquern. What comes after?”

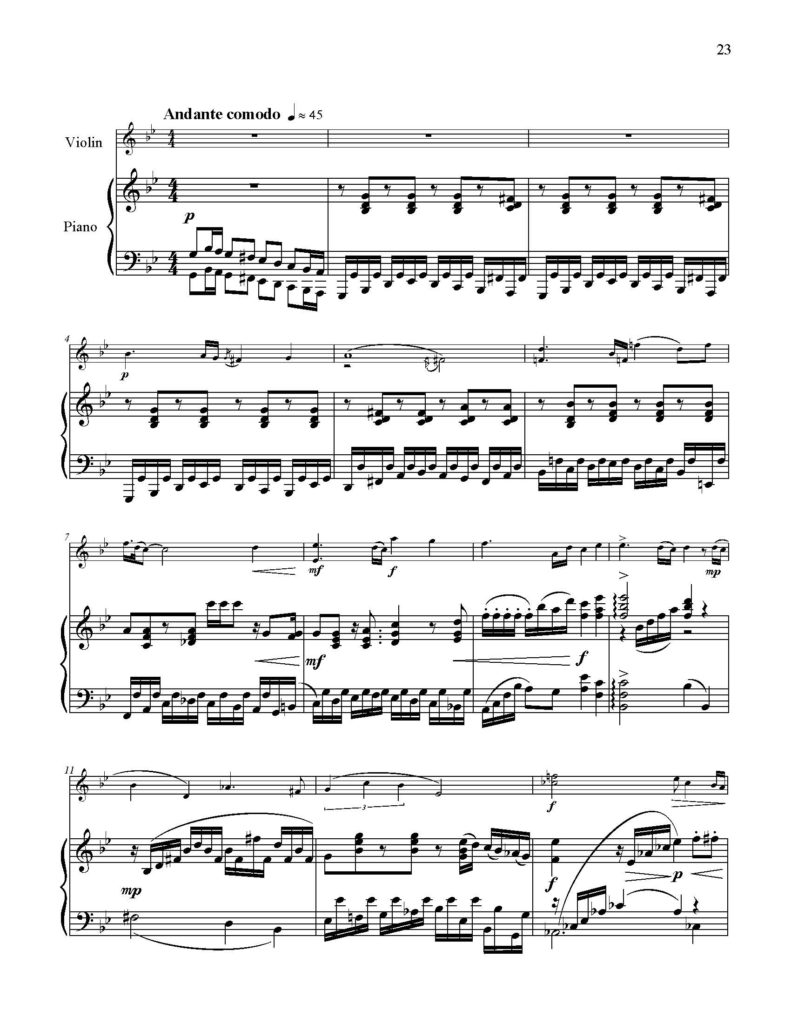

This is the final music of Quiquern. At the end of the story, the dogs lead the boy and girl to a crack in the ice where seals are coming up for air. They kill as many seals as they can carry, and hurry them back to the village. The people rejoice as famine is averted just in time. They sing and light candles made of seal fat.

Kotuko and the girl took hold of hands and smiled,

for the clear, full roar of the surge among the ice

reminded them of salmon and reindeer time

and the smell of blossoming ground-willows.

Even as they looked, the sea began to skim over

between the floating cakes of ice,

so intense was the cold;

but on the horizon there was a vast red glare,

and that was the light of the sunken sun.

It was more like hearing him yawn

in his sleep than seeing him rise,

and the glare lasted for only a few minutes,

but it marked the turn of the year.

Nothing, they felt, could alter that.

This ending seems to think of itself as a happy ending. But that’s not really what it is. It’s not a sad ending either. The village is well-fed for today, and their way of life continues the way it has for a thousand years. There is something truly magical about that. But what happened this winter will happen again. The village’s survival is always balanced precariously upon a precipice. As the camera pans out, we are reminded that all around the happy village is an endless frozen desert, cruel and dark, and so very cold. A single warm ember in a vast field of ice.

Perhaps that is a metaphor for all of humanity. Everything that we do and everything we care about and everything we’ve ever created and everything we remember and cherish is but a tiny ember in the blackness of space. How hard we all try to keep it lit; how vast and cold and uncaring is the universe.

Does that mean we shouldn’t live our lives to the fullest? Of course not! It’s even more reason to appreciate life. The feel of a baby’s skin on one’s cheek, the laughter of a life-long friend, the warm embrace of a lover, the taste of well-prepared food, the memories of good times, the hopes and dreams and aspirations we all nurture in our hearts; these things keep us warm and snug through the winters of life, even if deep down we know that the dark need not attack us directly to see us finally defeated, it need only wait.

A Letter to My Father

This evening I added the finishing touches to a piece I composed back in 2008, “A Letter to My Father.”

This piece is actually the third movement from my string quartet “Jackdaw.” Therefore at its heart it is based on the life and writings of Franz Kafka, like all the other music in that quartet. However this music has special meaning for me as well (also like all the music in that quartet). It feels especially meaningful during this current time in my life, when my own interactions with my father have become so very strange.

Kafka’s Letter to his Dad

When Kafka was about 36, he wrote a nasty letter to his dad. Apparently his father Hermann was a pretty difficult guy, constantly ridiculing Kafka for being a weakling, while refusing to care one bit that his son was a genius. Kafka’s stories are real mind-benders. The realities they portray are just “off” enough that they feel like they could be real life. One can recognize the landscape, envision oneself living in that world, but something in the reality is very wrong. Sometimes it’s hard to put one’s finger on… but impossible to ignore. Like the work of H.P. Lovecraft, the stories have the power to make one doubt one’s own world, to make one doubt mankind as a whole. It’s delicious writing, and frankly still horrifying to this day. Despite young Franz’s clear talent, Poppa Kafka just didn’t respect his son, and he made that known at every opportunity.

By age 36, Franz was tired of Hermann’s crap. He busted out some paper and really let Dad have it, for 45 hand-written pages. In his own way, Kafka believed that this letter would help heal their relationship, but in reality the letter was full of complaints, accusations, and invective. He plumbed the depths of his own hurt, and wrung the emotions out onto the page. If the letter is to be believed, Hermann was a toxic and narcissistic hypocrite, an abusive tyrant who never gave his fragile son even a kindly word or friendly look in all his life. The writing is heart-breaking and so very relatable, ripe as it is with a certain timeless pain that has been felt by so many sons across so many generations.

In one episode, Kafka describes a traumatizing experience from his childhood: one evening at bedtime he was begging his father for some water (perhaps even being a bit bratty about it), when his father, always a large and intimidating man, burst into his bedroom without warning and, in a rage, grabbed the small boy and locked him outside on the balcony with nothing on but his thin cotton sleep shirt. Kafka writes:

I was quite obedient afterwards at that period, but it did me inner harm. What was for me a matter of course, that senseless asking for water, and the extraordinary terror of being carried outside were two things that I, my nature being what it was, could never properly connect with each other. Even years afterwards I suffered from the tormenting fancy that the huge man, my father, the ultimate authority, would come almost for no reason at all and take me out of bed in the night and carry me out onto the balcony, and that meant I was a mere nothing for him.

Franz Kafka, from Letter to His Father

Not only is this a sad story of parental mismanagement and emotional scarring, but it is also such a great insight into why so much of Kafka’s writing features nameless, faceless authority figures who carry out irrational sentences with a total lack of empathy or emotional connection. Moments that feature characters like that are some of the more disturbing vignettes from his stories; they make it all too easy to picture oneself being dragged away by faceless agents of the state who have no sense of human morality or concern for life. Kafka was able to translate his tragic daddy issues into terrifying metaphors for what it’s like to live in modern society. Now THAT’S how to cope with a bad upbringing.

Let’s all write letters to our dads!

Funny story: I had to send a letter to my own father recently. Mine was not as nasty as Kafka’s, nor was my father anywhere near as abusive as Hermann. But father-son relationships can be all varieties of strange, and mine definitely falls on that spectrum. I won’t go into the details here, but suffice it to say that at pretty much the same age as Kafka when he wrote his letter, I felt compelled to write a letter to my dad that I wish I didn’t have to write. It delivered the message, though I’m not sure it did anything to heal our relationship.

When Kafka completed his letter, he hand delivered it to his mother, and asked her to bear the letter to his father. Her mother read it once and immediately decided to hide it forever. As much as Kafka might have hoped his manifesto would help heal old wounds, his mother felt differently, and refused to take any part in provoking the monumental explosion that would likely follow should Hermann ever read it. My own letter was delivered directly to my father, though I’m actually not sure he read it. One can never know these things when direct communication becomes impossible.

Long story short, this music ain’t just about Kafka. I hope someday someone writes about how I skillfully took my familial pain and transformed it into timeless art we can all relate to. Whether or not that ever happens, I will say this: writing the music always makes me feel better.

Letting Myself Fall

One time I let myself fall. Down, down, down into the mud I went, slowly, ever so slowly, until my head was under, and I was lost for a time.

One time I lost everything I’d ever written. This is what I wrote next.

The date was September 24, 2006, my 22nd birthday. Erica and I decided to have a picnic in Meadow Park, share a bottle of wine, and take a nap. It was during this wine-induced nap that somebody walked into our house, in the middle of the day no less, while we slept peacefully in the bedroom, and stole my laptop.

This particular laptop happened to contain all the music I had ever written up to that time. Was it backed up somewhere? Of course not. After all, my laptop had never been stolen before, so why would I need to back up everything I’d ever created. Nope, it was all right there, and someone stole it right out of my house in broad daylight. I never saw it again.

The thief did not take our DVD player. He did not take our television. He did not take my car keys or the stereo either. He didn’t even take the laptop’s power cord. Just the laptop. And of course my very reason for living.

When I awoke from my cat nap, it took me a good half hour to realize the laptop was gone. I won’t try to put into words what went through my head except to say this: all of my art was destroyed that day. I had no website, no hard drive, no printed copies. I felt like a victim of fire. I was completely alone with my grief.

Ok I was able to salvage a couple things. While ravaging through my belongings looking for any sheet music I could find, I miraculously discovered some printed pages stuffed down into a drawer. The pages were the original versions of what would later become the 3rd and 4th movements of my first piano sonata. I was also able to copy down from memory the scraps that would later become the last movement of my first string quartet. Other than those tidbits, everything else was taken forever. My entire career as a composer up to that point was a blank page.

It took me a long while to get into the headspace of composing again. When I finally did, for some reason this jolly music is what came out. Maybe it was the sense of hope that even though I had lost all my previous work, I could still write something new, that my life as a composer was not actually over. As I continued to write this, my hope only continued to grow. By the time it was done, there was a part of me that was glad I had lost my old work, which is a weird thing. In a way, it was a freeing experience to lose my student work. It allowed me to try new things, and not feel weighed down by whatever direction I had chosen in the past. I think that’s what this music is trying to say.

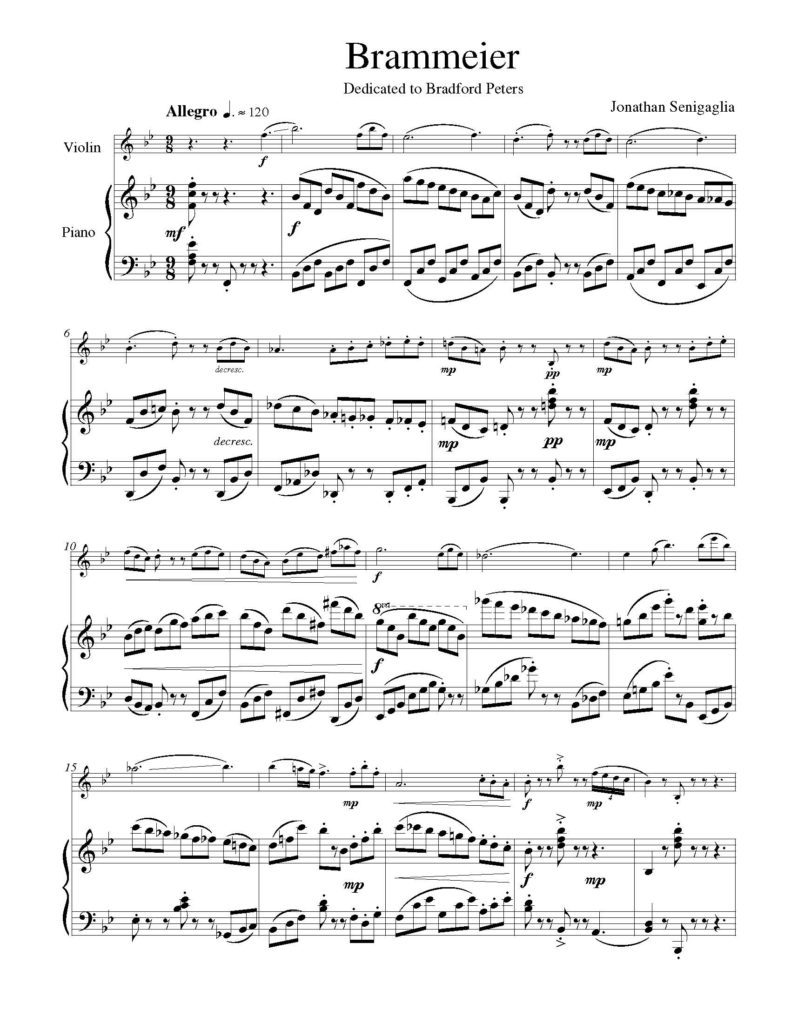

Music that reminds me of drinking absinthe in Prague

Excerpt from journal.

Dated July 27, 2012 – Prague

On a recommendation from a bartender, we headed toward a pub away from the city center, on some twisted alley or another. Our bellies were full of dumplings and gravy, our hearts starving for adventure. We waltzed into a well-lit bar and took a drink of the scenery.

The air was viscous with cigarette smoke. I immediately felt as though I were deep deep underwater, in a pub at the bottom of the sea. The rowdy conversations of the crowd drifted slowly toward me; from a distance I could see the words coming my way, yet still I couldn’t quite make them out. Men and women emphatically slapped the tables in laughter, rattling the half empty glasses and late night coffees and honey cakes, sending them floating away around the room. Others sipped their absinthes knowingly, balancing their cigarettes so delicately atop their outstretched fingers.

Ah Prague, ah absinthe. In honor of Bohemia we ordered two drams of the green concoction. Actually it wasn’t green… but it did smell like licorice, and it burned, burned!

It suddenly became very warm in that bar.

I was taking in my hazy surroundings when I saw her, sitting silently beside a red couch. She wasn’t outlandish, wasn’t putting herself out there, just relaxing and blending into the scenery. I’m not sure anyone else in the room even noticed her.

She was a thing of beauty.

She had a strong yet elegant frame made of fine wood panels. Her golden pedals glimmered and winked at me, beckoning me. Her keys were made of real ivory, an authenticity that can not be faked. This was no tourist attraction. This was the real shit, the soft underbelly, the pearl, that hard-to-reach part of your back. I was suddenly helpless against a mighty river of desire. I let it take me, wash over me, sweep me away.

I could tell right away that she was played regularly; all the tell-tale signs were present. The keys were bare and open for all the world to see, draped flirtatiously like freshly painted fingernails. The bench was pulled out, a bare leg peeking from beneath a knee-length skirt. However refined she may have seemed to an untrained eye, I could see from across the room how much she loved to be touched, that her strings were tight, her music sweet and pure.

I realized I was in a conversation with a man at the bar. While pretending to chat, my gaze kept wandering to her quiet corner of the room. She stared back at me unabashed. I wanted to put my hands on her that very moment, to know her secrets.

Erica looked at my face and read me like a book. I was lost already and there was no point trying to pull me back. We locked eyes and she signaled that I was free to go. I immediately moved to the instrument.

When I touched, I fell into a trance. Twenty minutes of absinthe-fueled dream music left my body.

Dumplings and cigarettes and alleyways. Twisting streets and beggars with their faces in the dirt. Pianos and absinthe and my wife’s soft skin. Love and travel and hunger and… feeling so lost that you forget what country you’re in.

The Painted Bird

When I read The Painted Bird by Jerzy Kosiński, it disturbed me, in that special way that only great literature can. It tore my brain up, left me feeling very uncertain about who I was, about my own species. This music just had to come out.

Music that reminds me of dog sitting

I wrote this on a ranch. I wrote this at the radio station, late late at night. It’s a song of love. It’s a song about feeling alone.

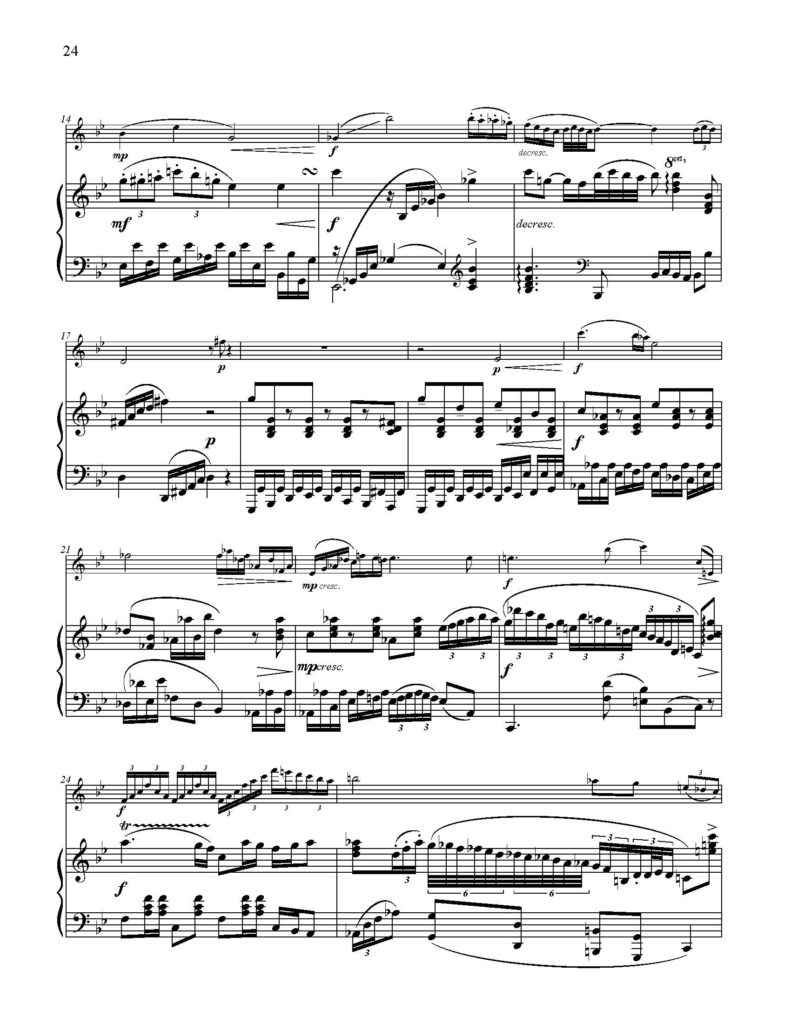

On the day I finished it, I also finished On Chisel Beach by Ian McEwan. This music wrapped itself around that story, and both were planted deep into my brain. Both the music and that story complain and ache and worry, they both drag it out when it doesn’t need to be that complicated. Both improve with age, with patience, with repetition.

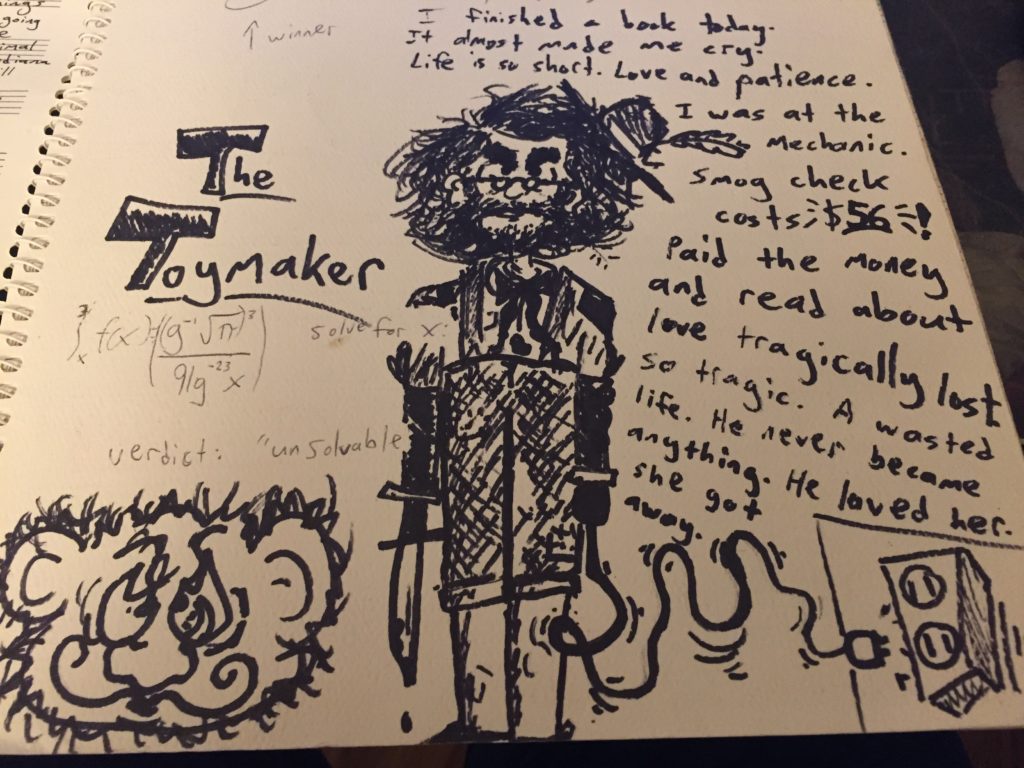

On the day I finished it, I drew this picture:

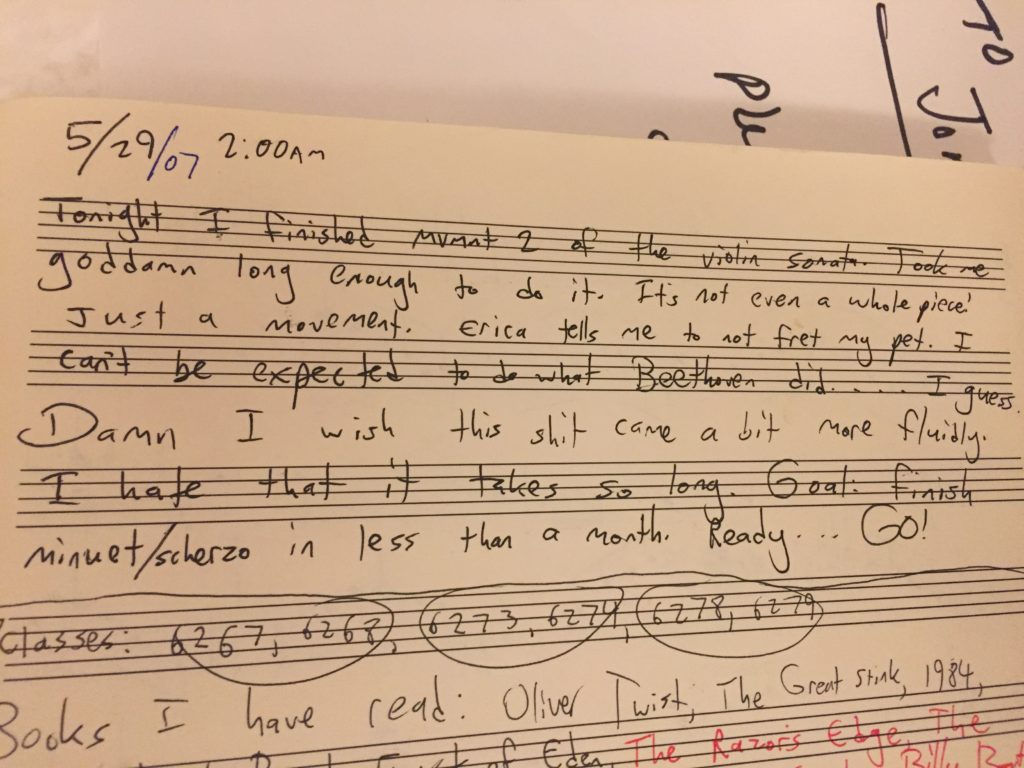

I also fretted about composing too slowly:

Writing words on sheet music is easier than writing music. Maybe I just need to write music as often as I write words.

This song reminds me of sitting up until all hours of the night, on a couch that wasn’t my own, in a strange house, watching WWII documentaries and checking to see if we’d accidentally let the coyote eat the cat.

It reminds me of the last grasping days of college. I was spending most of my time grasping, grasping at what?… grasping at something.

It reminds me of emerging from a dark cavern to greet the morning sun. It reminds me of waiting, waiting, waiting to grow up.

Years and years and years after I finished the music, I played it for someone. She said, “You’re really starting to get good at this.” I pretended that the music was truly new.

Marshmallow

I created this song and video for my wife Erica for our ten year anniversary. It’s called “Marshmallow”.

Who Am I Stealing From Today? (David Wise)

In late 2017 I picked up Quiquern again and resolved to finish it for the last time. How many times had I called this project complete, only to pick it up again a year later and tinker, tinker? Well those days are done. If I can’t finish a project, like really finish it, how can I call myself a composer, or an artist for that matter? By the New Year had I hammered out the first fragment (now equipped with a Village Dance section) and finally turned the second fragment into a real piece, rather than just a collection of unconnected ideas.

In early January, full of fresh energy and creative juice, I saw the music in a different light and dove headfirst into some new material. In two days I created an entirely original fragment: The Singing House.

Fragment 3: Quaggi – The Singing House

Come on a musical journey with me.

On the far side of the village is the Quaggi – The Singing House. Only men may enter; it is where they go to pray. In times of plenty, the men sing hearty songs of gratitude to the various gods of the Arctic. In times of desperation, they fall into a trance of smoke and dark and sweat and hunger. Arms linked, stomping the holy ground, repeating of the same syllables, the great hunters of the village reach for the gods with outstretched arms.

What does a 10 year old boy imagine of this place? Banned from entering, just like the women, but knowing in his heart, unlike the women, that one day he will be granted entry into the inner sanctum, a young boy of the village can only guess what goes on inside that large tent. He hears from a friend that the sorcerer sings his magic songs and calls upon the Spirit of the Reindeer, and his songs make the wind blow and the ice crack to reveal the seal below. Anxiety and yearning and fear wiggle through his body. One day he would take his place in the Quaggi and learn the secrets of the hunters.

But at fourteen an Inuit feels himself a man, and Kotuko was tired of making snares for wild-fowl and kit-foxes, and most tired of all of helping the women to chew seal-and deer-skins (that supples them as nothing else can) the long day through, while the men were out hunting. He wanted to go into the quaggi, the Singing–House, when the hunters gathered there for their mysteries, and the angekok, the sorcerer, frightened them into the most delightful fits after the lamps were put out, and you could hear the Spirit of the Reindeer stamping on the roof; and when a spear was thrust out into the open black night it came back covered with hot blood.

I should also note that I openly plagiarized the work of another composer in this piece: David Wise, who wrote all the music from Donkey Country (1 and 2). Here’s the tune I stole:

So good right?

The music from this game was the running soundtrack of my childhood. When I was in middle school, I used to pretend I was in a band (perhaps in some jazzy night club) performing this very song. This music shaped me and my compositional style. I feel honored to sample this man’s music.

The form of “Quaggi” is reminiscent of video game music. The first section is a long musical segment consisting of variations on a couple themes. It then repeats. In fact it could repeat on loop and just BE video game music.