This evening I added the finishing touches to a piece I composed back in 2008, “A Letter to My Father.”

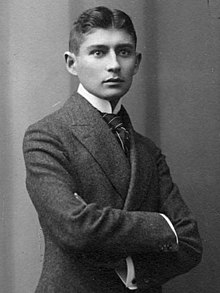

This piece is actually the third movement from my string quartet “Jackdaw.” Therefore at its heart it is based on the life and writings of Franz Kafka, like all the other music in that quartet. However this music has special meaning for me as well (also like all the music in that quartet). It feels especially meaningful during this current time in my life, when my own interactions with my father have become so very strange.

Kafka’s Letter to his Dad

When Kafka was about 36, he wrote a nasty letter to his dad. Apparently his father Hermann was a pretty difficult guy, constantly ridiculing Kafka for being a weakling, while refusing to care one bit that his son was a genius. Kafka’s stories are real mind-benders. The realities they portray are just “off” enough that they feel like they could be real life. One can recognize the landscape, envision oneself living in that world, but something in the reality is very wrong. Sometimes it’s hard to put one’s finger on… but impossible to ignore. Like the work of H.P. Lovecraft, the stories have the power to make one doubt one’s own world, to make one doubt mankind as a whole. It’s delicious writing, and frankly still horrifying to this day. Despite young Franz’s clear talent, Poppa Kafka just didn’t respect his son, and he made that known at every opportunity.

By age 36, Franz was tired of Hermann’s crap. He busted out some paper and really let Dad have it, for 45 hand-written pages. In his own way, Kafka believed that this letter would help heal their relationship, but in reality the letter was full of complaints, accusations, and invective. He plumbed the depths of his own hurt, and wrung the emotions out onto the page. If the letter is to be believed, Hermann was a toxic and narcissistic hypocrite, an abusive tyrant who never gave his fragile son even a kindly word or friendly look in all his life. The writing is heart-breaking and so very relatable, ripe as it is with a certain timeless pain that has been felt by so many sons across so many generations.

In one episode, Kafka describes a traumatizing experience from his childhood: one evening at bedtime he was begging his father for some water (perhaps even being a bit bratty about it), when his father, always a large and intimidating man, burst into his bedroom without warning and, in a rage, grabbed the small boy and locked him outside on the balcony with nothing on but his thin cotton sleep shirt. Kafka writes:

I was quite obedient afterwards at that period, but it did me inner harm. What was for me a matter of course, that senseless asking for water, and the extraordinary terror of being carried outside were two things that I, my nature being what it was, could never properly connect with each other. Even years afterwards I suffered from the tormenting fancy that the huge man, my father, the ultimate authority, would come almost for no reason at all and take me out of bed in the night and carry me out onto the balcony, and that meant I was a mere nothing for him.

Franz Kafka, from Letter to His Father

Not only is this a sad story of parental mismanagement and emotional scarring, but it is also such a great insight into why so much of Kafka’s writing features nameless, faceless authority figures who carry out irrational sentences with a total lack of empathy or emotional connection. Moments that feature characters like that are some of the more disturbing vignettes from his stories; they make it all too easy to picture oneself being dragged away by faceless agents of the state who have no sense of human morality or concern for life. Kafka was able to translate his tragic daddy issues into terrifying metaphors for what it’s like to live in modern society. Now THAT’S how to cope with a bad upbringing.

Let’s all write letters to our dads!

Funny story: I had to send a letter to my own father recently. Mine was not as nasty as Kafka’s, nor was my father anywhere near as abusive as Hermann. But father-son relationships can be all varieties of strange, and mine definitely falls on that spectrum. I won’t go into the details here, but suffice it to say that at pretty much the same age as Kafka when he wrote his letter, I felt compelled to write a letter to my dad that I wish I didn’t have to write. It delivered the message, though I’m not sure it did anything to heal our relationship.

When Kafka completed his letter, he hand delivered it to his mother, and asked her to bear the letter to his father. Her mother read it once and immediately decided to hide it forever. As much as Kafka might have hoped his manifesto would help heal old wounds, his mother felt differently, and refused to take any part in provoking the monumental explosion that would likely follow should Hermann ever read it. My own letter was delivered directly to my father, though I’m actually not sure he read it. One can never know these things when direct communication becomes impossible.

Long story short, this music ain’t just about Kafka. I hope someday someone writes about how I skillfully took my familial pain and transformed it into timeless art we can all relate to. Whether or not that ever happens, I will say this: writing the music always makes me feel better.